This little girl has been making eye contact with us for almost exactly four hundred years. She was the inspiration behind this year’s exhibition, Picturing Childhood: A New Perspective at Chatsworth (16 March - 6 October).

The Artist’s Daughter, Magdalena de Vos, by Cornelis de Vos, about 1623-24, oil on canvas

She – Magdalena – has been hanging quite high on a wall on the visitor route for many years. She was around three years old when her father painted this. Looking up at her from below, she had the appearance of individuality, awareness and expressiveness (what we might today call ‘agency’) and this sparked our curiosity. For a small child looking down at us from the 17th century, the possibilities to connect her with children across time seemed strong.

So, it was with some relief that, when we finally saw her at ground level as the exhibition installation got underway, we found that Magdalena has even more presence when you meet her face-to-face.

I hope she will be the first thing that catches a visitor’s eye as they enter the State Bedchamber. Like many other children featured in the exhibition, she looks as if she knows her own mind. Her father’s skill in painting materials and objects (the lace collar and flowers in Magdalena’s hair for example) does not distract from her personality. He has echoed the colours of her dress and flowers to render golden highlights in her hair and rosy cheeks.

The endearing and technical quality of this portrait sparked a conversation around how well we could tell a story of childhood using the strengths of the Devonshire Collections at Chatsworth.

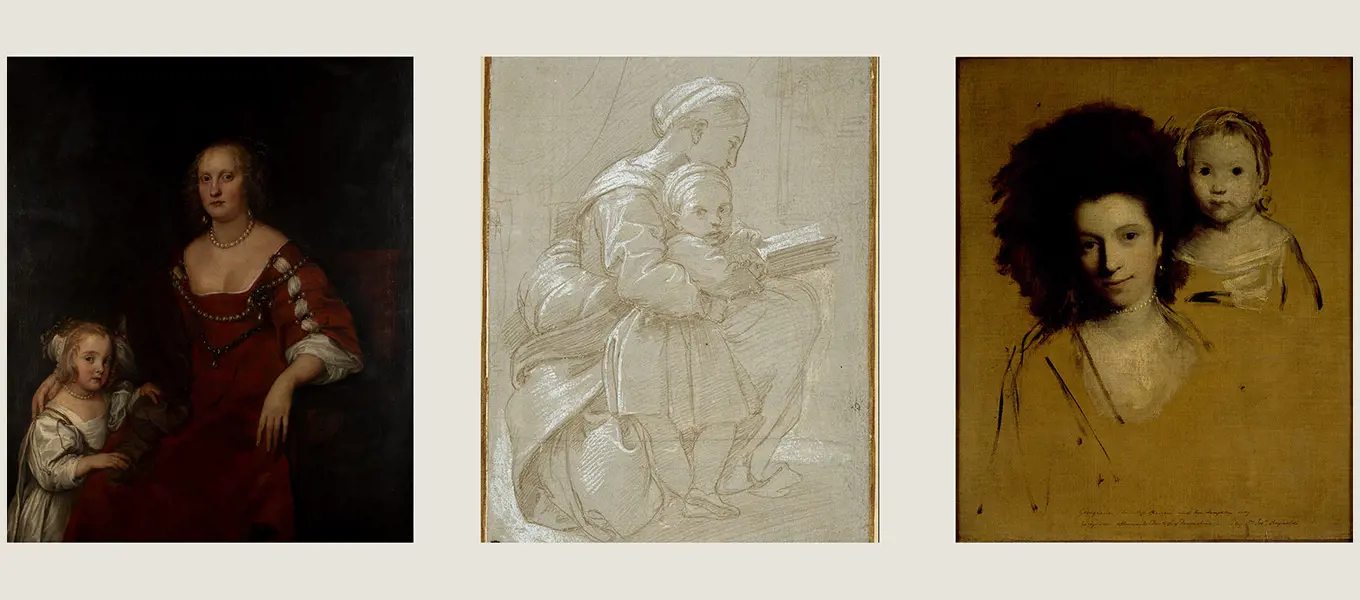

When we started looking, we found that we could picture childhood through the major historical periods, from Tudor to the present day. We have some exquisite examples by well-known artists including Raphael, Van Dyck and Reynolds and you'll see these if you visit.

Sir Anthony van Dyck (left), Raphael (centre), Sir Joshua Reynolds (right)

Is it all in the eyes?

Something about these three works - regardless of the artist, child represented, or time - started us thinking about what it feels like when a child holds your gaze. Think of the times you have sat opposite a baby or toddler on a bus or train, or behind them in a queue in a shop. Or, the way your own child, or a child in your life, locks eyes with you.

Babies and young children stare out of curiosity as they begin to engage and explore the world around them; everything is new and they are developing their social and interaction skills. 'Staring' is a form of communication with the world.

Many of the children in the exhibition meet our gaze but others do not – and when they do not, we can feel as if we have intruded into a special, intimate or introspective moment.

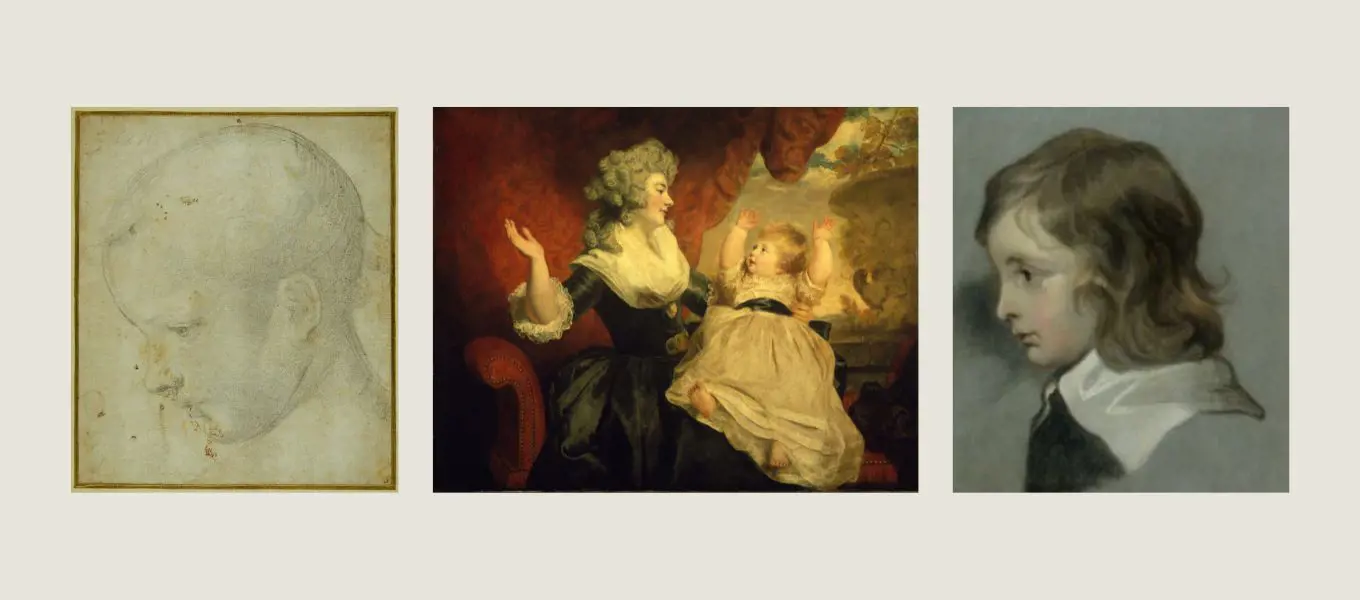

Fra Bartolommeo (left), Sir Joshua Reynolds (centre), Follower of Peter Lely (right)

Whether well-known or new to you, artists can be at their least restrained or formal when depicting children and we have shared examples of this throughout the exhibition.

Reynolds's portrait of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, with her daughter, Lady Georgiana Cavendish (above, centre) is a good example of this. An unusual composition for Reynolds, it captures a moment of spontaneous and joyful reaction between mother and child.

There are accounts of Reynolds preparing to draw and paint children. These describe him as joking and playing around with children in his studio, to set them at ease. He was happy to talk to them ‘in their own way’ which we can imagine might mean baby talk or playing with sounds to entertain them.

There is certainly a shift in representation when we look from Tudor and Stuart to Georgian-era pictures of children and childhood. We can visually touch on humanist (Erasmus) and enlightenment (modern social contract) theories of education (Locke and Rousseau). This moves our thinking from representation to experiences of childhood.

We know that Reynolds – and other artists of this time – had read, and were interested in, the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau put forward ideas about child rearing and education, which advocated play, being outdoors, learning from experience and practical activity as opposed to formalised learning that is delivered to a plan by a teacher or instructor. Rousseau’s theories may have had an influence on the 5th Duke and Duchess Georgiana as well as on the artist.

Looking at the artworks featured in Picturing Childhood has prompted a re-centring of narratives across historic periods. What were these children’s lives like? Did they have close family relationships with parents and siblings? Were they happy? What were their interests and did they have any choice in this?

Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork, and His Wife Lady Dorothy Boyle with Three Children, Jean-Baptiste van Loo, 1739, oil on canvas

This painting (above), ending the Georgian section, considers many of the themes running through the exhibition.

The group portrait features three children whose lives in the same household will have been quite different. We know a lot about the two girls and less about the boy, a child of colour.

As part of our exhibition development process, we have formed an advisory group comprised of colleagues from across our visitor-facing teams and members of the public with lived experience. As a group, we have discussed how to develop interpretation around this portrait, how to have conversations and confidence in engaging the public with the subject of childhood and empire, and what the legacy of this temporary exhibition will be, such as a commitment to research; extending layers of interpretation across our visitor route and future outreach work.

The story is currently incomplete and visitors to Chatsworth will be able to follow the narrative as it develops throughout 2024. We will be sharing the work of our advisory group and new research by Dr Edward Town of Yale Center for British Art, USA at the end of the exhibition (October 2024).

The last section of the exhibition is memories of childhood, and what better way to share this than with photographs, books and Victorian dinner menus from our archive. For this last section of the exhibition visitors can flick through a family photo album, watch a description of children capering and frisking (from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice) come to life and strike a pose in the Sculpture Gallery before heading into the garden with a ‘Ways to Play’ trail.

Contemporary artists and designers have created playful responses to childhood and curiosity to bring the exhibition to the present day. There’s a restful moment near the start of the visitor route, with Peter Newman’s Skystation in the Inner Court, and Tasha Marks of AVM Curiosities has recreated aromas of dinners past in the Great Dining Room. Abigail Reynolds series Anthronaut taps into new perspectives. Hawk gives you the chance to see a hawk’s eye view of The Painted Hall whilst two installations in the garden further develop an idea inspired by T.H White’s The Sword in the Stone, in which Merlin transforms Arthur into different birds and animals to teach him about the world.

Picturing Childhood: A New Perspective at Chatsworth has no conclusion – one of the great delights of this exhibition has been working with children to develop some of the content. Pupils from Athelstan Primary School feature in the animated film linked to Pride and Prejudice, and pupils and teachers from Whittington Moor Nursery and Infant Academy curated our ‘read together’ seating area, with their favourite books.

There are long-held views that childhood is a modern idea and that in the past, children were considered miniature adults. Childhood may have been different yet there are some aspects of it – such as curiosity and play - that remain constant across time.

Visit Picturing Childhood: A New Perspective at Chatsworth from 16 March to 6 October.

You may also like...

Picturing Childhood - the exhibition

Until 6 October

Learn more about Picturing Childhood: A New Perspective at Chatsworth and book tickets to visit.

Curator Tour: Picturing Childhood

22 July & 18 September

A guided tour of Picturing Childhood led by exhibition curator, Gill Hart.

A Childhood Archive

31 May & 6 September

Explore the history of childhood at Chatsworth spanning four centuries in letters and photographs preserved in the archives.

Picturing Childhood blog series

Delve deeper into the themes of this year's Picturing Childhood exhibition and the works on display.