Take a look at this drawing as a whole (try not to zoom into details too soon). Make a note of what you can see:

- In the foreground

- In the midground

- In the background

- On the left-hand side

- On the right-hand side

Now, decide what you feel the most dominant feature of the drawing to be.

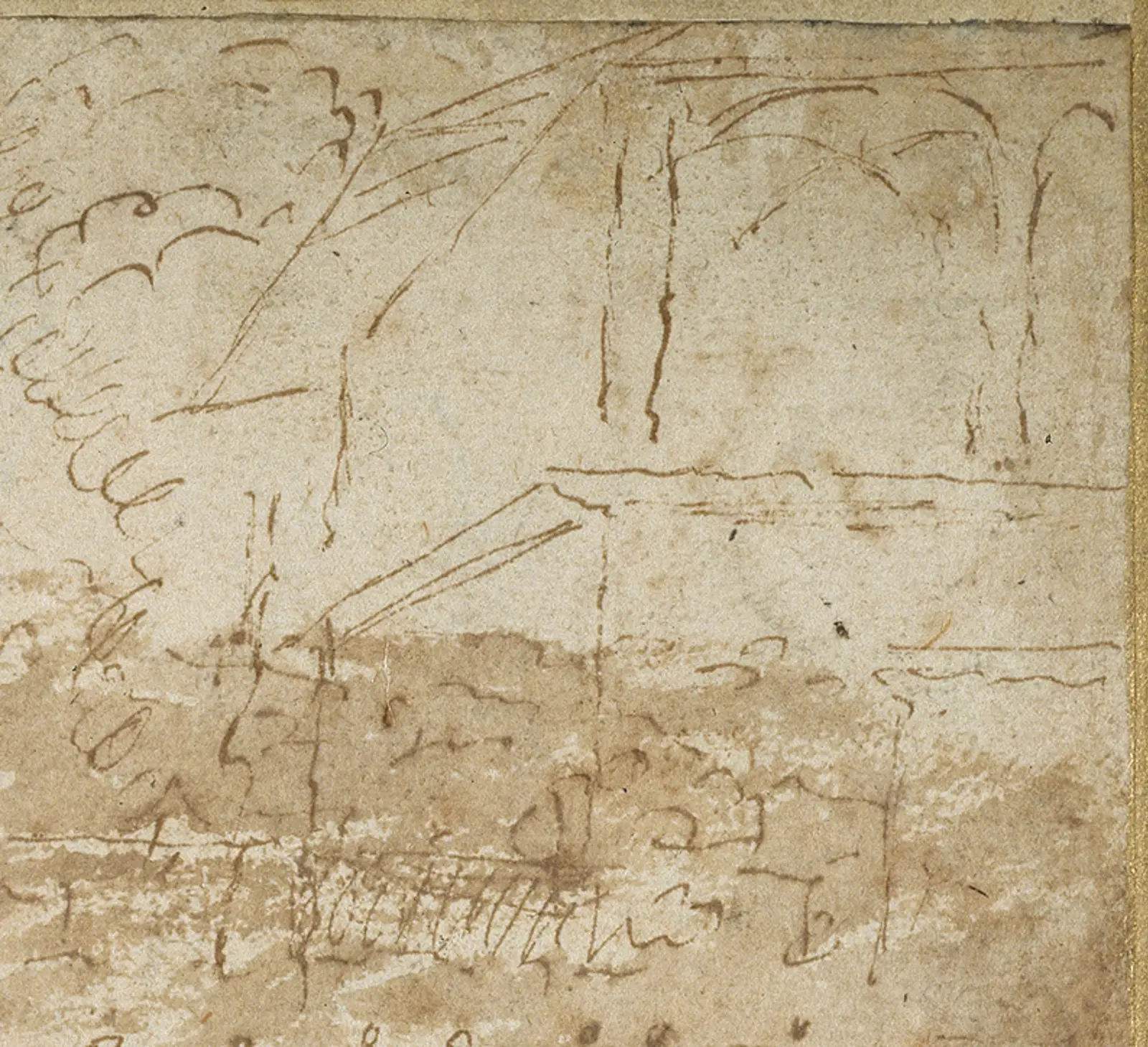

There is a lot to take in here. A large number of active figures populate the drawing. Perhaps the interlocking limbs and dynamic poses appeal to you. Alternatively, you might be drawn to the stability that the temple-like building lends to the composition. Let’s break this down.

The foreground

The foreground provides a staging area for the core of the narrative. Poussin’s subject is the abduction of the Sabine women. Historically, this subject was known as The Rape of the Sabines (rape being derived from the latin raptio – a term used to describe abduction and/or enslavement). This story is from classical history; there are six drawings and two paintings by Poussin on the theme. The legend of the Sabine Women is connected to the early history of Rome. Romulus, the founder of the city (shown on the left-hand side of this drawing), wanted to make sure the city would grow and flourish and to do this he needed to grow the population. He invited communities who lived nearby to the city under the false pretence of celebrating a festival. The Sabines arrived with their families and the young men of Rome attacked them and abducted many of the Sabine Women.

It was a popular subject among patrons and artists during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In the 17th century, when Poussin was alive (corresponding with the Baroque period) artists tended towards dramatic renderings of the story, with soldiers often on horseback gathering up protesting women.

Poussin’s style was influenced by Raphael and by classical antiquity.

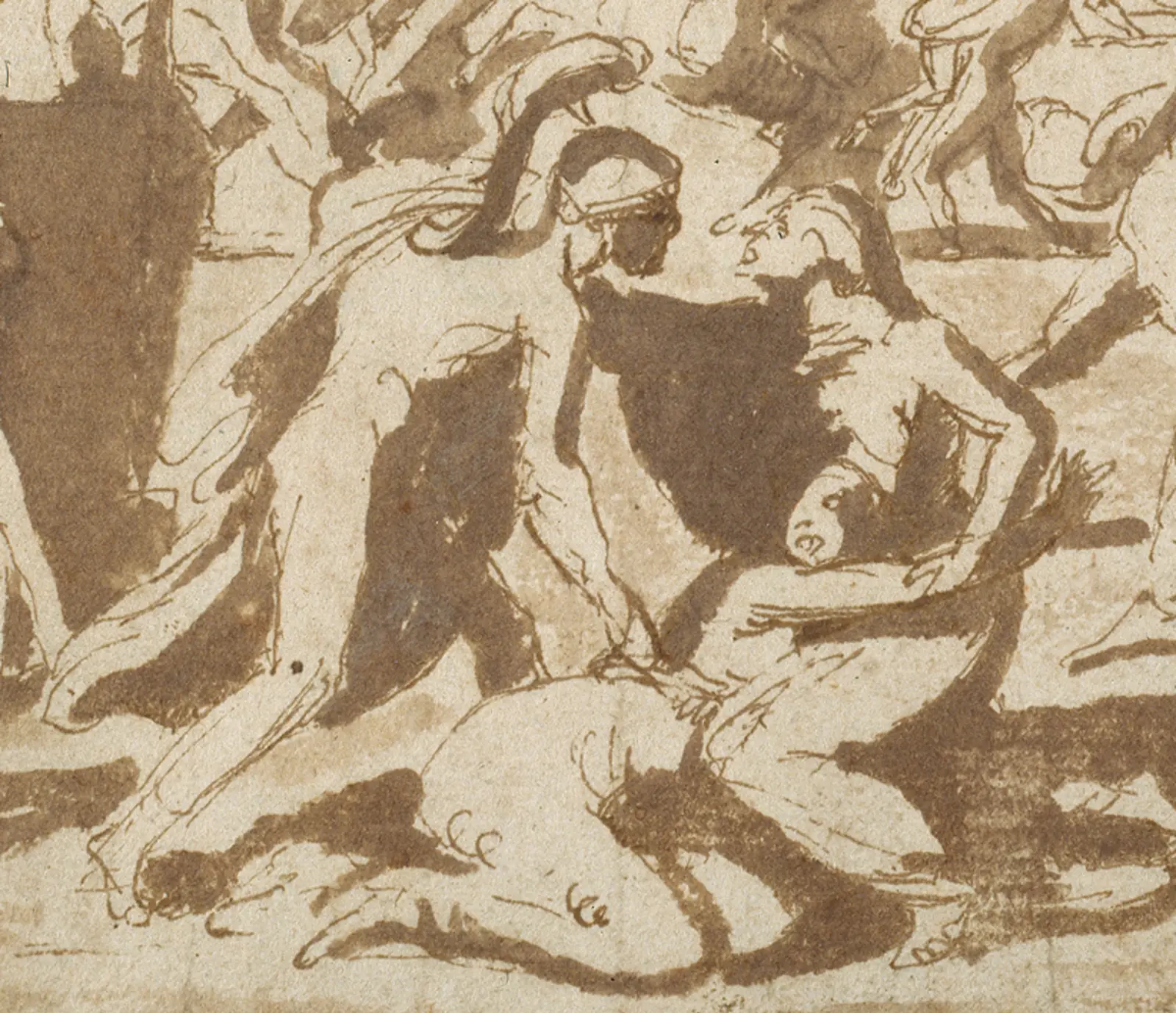

Focus in on the central group of figures in the busy foreground scene. Note that there is one very distinct item of costume/clothing: the unmistakable curvilinear crest of the helmet of the Praetorian Guard (a high-ranking Roman Soldier).

Another striking feature of this drawing is Poussin’s use of brown wash to distinguish light from shade and the volume of human form against void.

The foreground of this drawing is very busy with figures. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify groups and couples, who may serve different purposes in the composition and narrative.

In this central group, the dark area of wash between the lunging soldier and the woman before him draws our attention to the possibility that she may be fighting back. Is she attempting to defend her unmarried kneeling companion, who clings to her?

Look at these details of two figures to the left and right of the foreground.

Were it not for the subject of this drawing, we might think they were dancing together, such is the balletic nature of their poses. The strong diagonals lend the drawing a sense of movement. Looking closely, you will see that this has been achieved with minimal detail. There are no facial features and very few costume details.

There is however a strong sense of the rigour and geometry in Poussin’s planning and thinking and in how these figures relate to the composition around them. His use of a few strokes of wash minimally but effectively suggests the volume of a figure rotating in space, with body parts set in the shade or casting shadows.

There are two oil paintings of this subject by Poussin - take a look at them now.

Images: The Rape of the Sabines, oil on canvas, credit Louvre, Paris/Bridgeman Images; The Abduction of the Sabine Women, oil on canvas, credit Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York/Bridgemen Images

It’s tempting to imagine Poussin creating wax models of these figures, positioning them on board inside a box and then viewing them from many angles. Some of them seem to have made it into the final paintings as if seen from a different point of view!

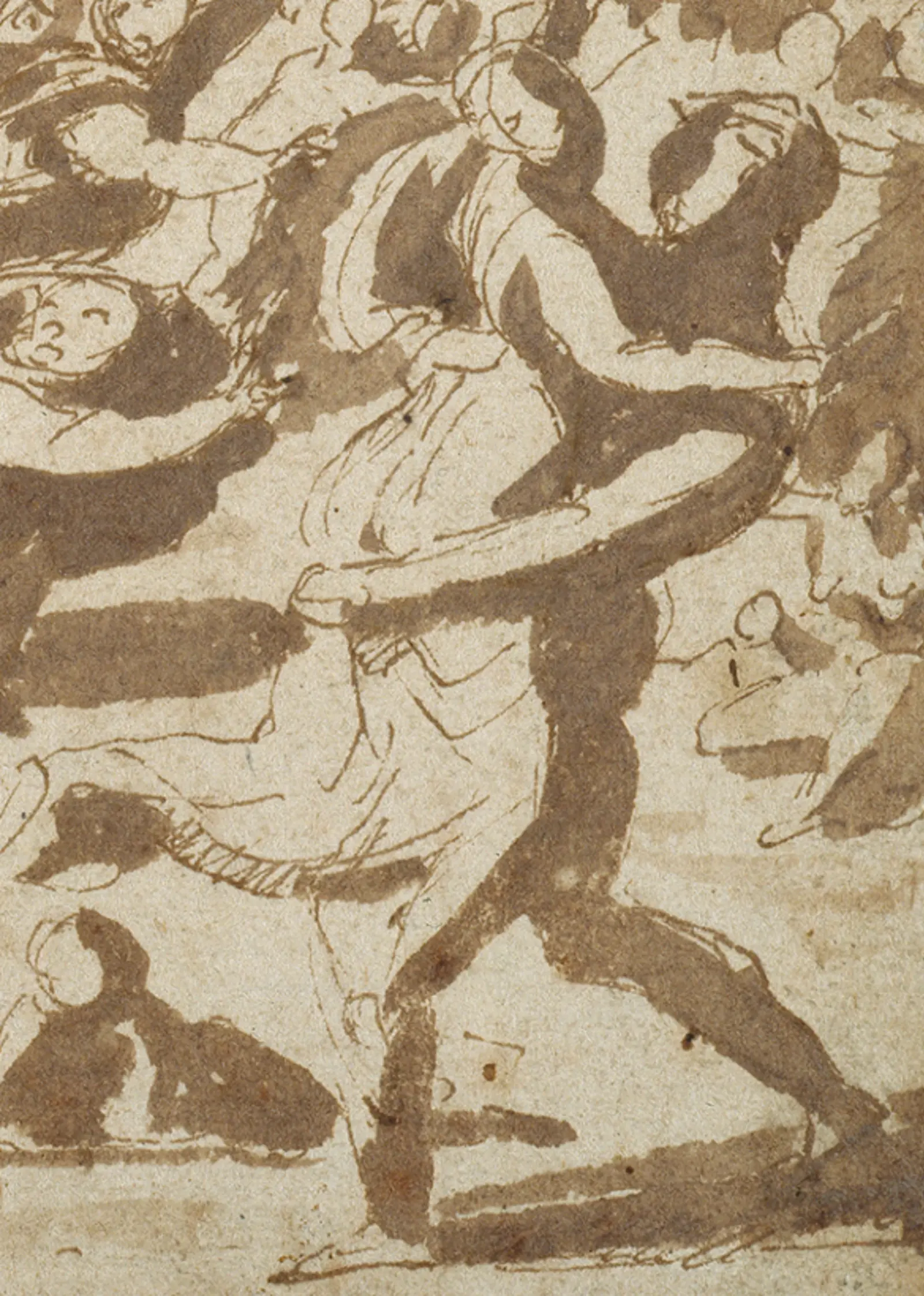

The middle ground

This may not have been the area of the drawing that you were attracted to first, but it is worth taking some time to notice the characteristics of this area of the scene.

We might describe the foreground of the scene as resembling a classical frieze. There is a sense of figures moving from left to right across the picture plane. Surviving classical friezes were a popular source for artists. In this example, also from the Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth, artist Biagio Pupini (active in the middle of the 16th century) has taken inspiration directly from a frieze panel from the Arch of Constantine, a Triumphal arch located in ancient Rome, between the Colosseum and Palatine Hill. The arrangement of figures in a procession from left to right can be detected.

Image: Biagio Pupini, Panel from the Arch of Constantine, pen and brown ink with brown wash

Looking from left to right across the middle ground of the Poussin drawing, the figures on the extreme left arguably belong to the foreground of the drawing. Larger in scale, and closer to us, one of them is almost pushed towards us by the expanse of dark wash surrounding his form (this is most likely Romulus, who raised his cloak to signal to his men that they should commence their attack). Again, note the way Poussin suggests light and dark – and depth – through the application of his chosen media.

Let’s remove those figures and concentrate on the middle depth of the drawing. What changes?

There is hardly any detail yet much gesturing going on. Marks made lightly with a pen suggest arms and weapons raised in attack and defence.

As the attack leads off into the distance, cursory loops and curves of pen present nothing more than visual code. Our eyes and brain must do the rest, to build these pen marks up into notational human figures. Poussin appealed to the mind and not the eye.

Later in life Poussin wrote ‘Observations on Painting’, describing what he felt the fundamental aims of the art form were. He emphasised expression and clarity, avoiding all unnecessary detail.

Raised arms, waving hands, tilted heads: these details appeal directly to us and communicate Poussin’s preoccupation with the depiction of emotion through gestures, poses and expressions. By looking closely at some of these details you might be able to pick out some connections between this austere classical artist from the 17th century and some of his modern successors such as Picasso and Cézanne.

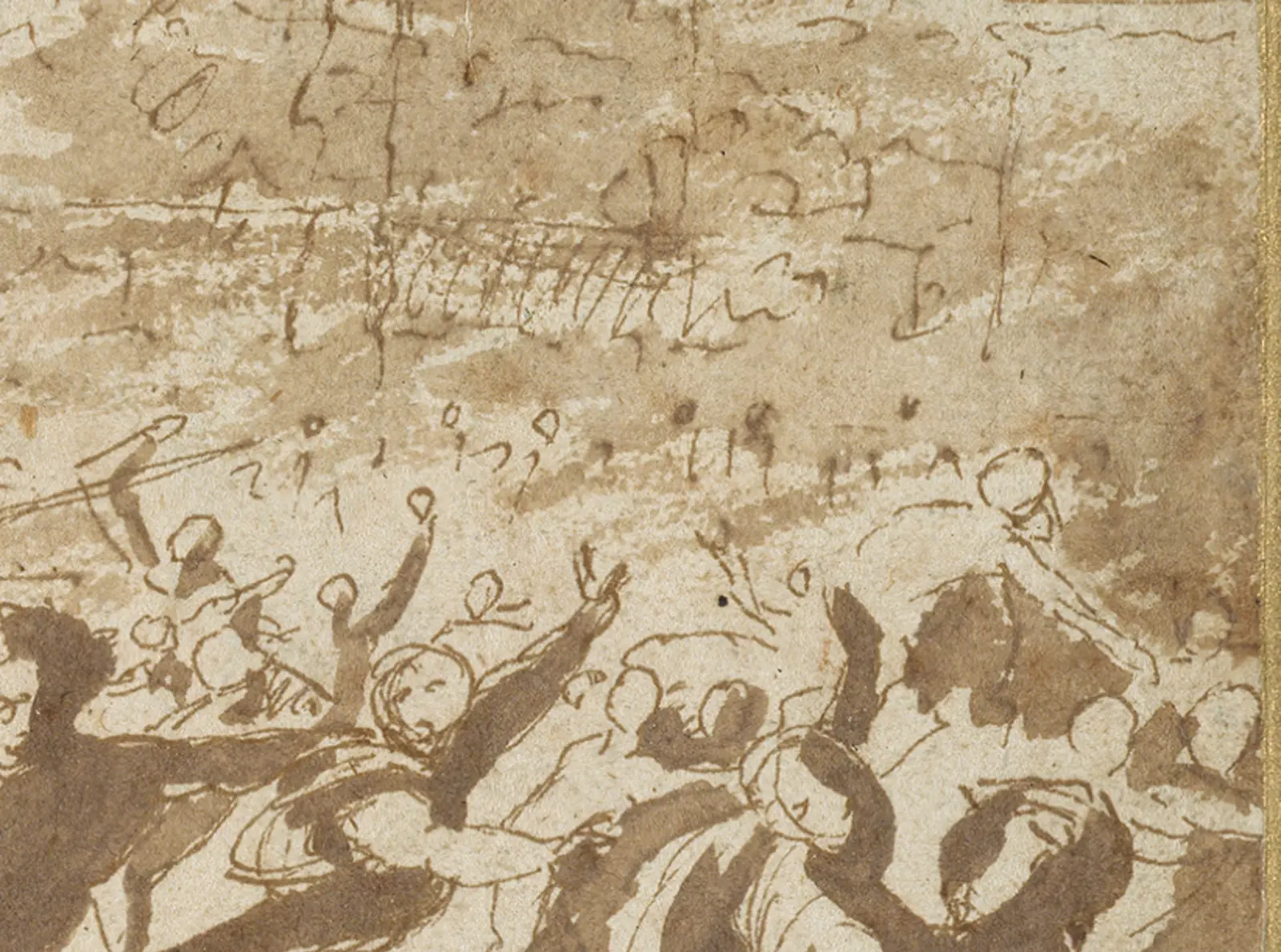

The background

How many architectural structures can you make out here?

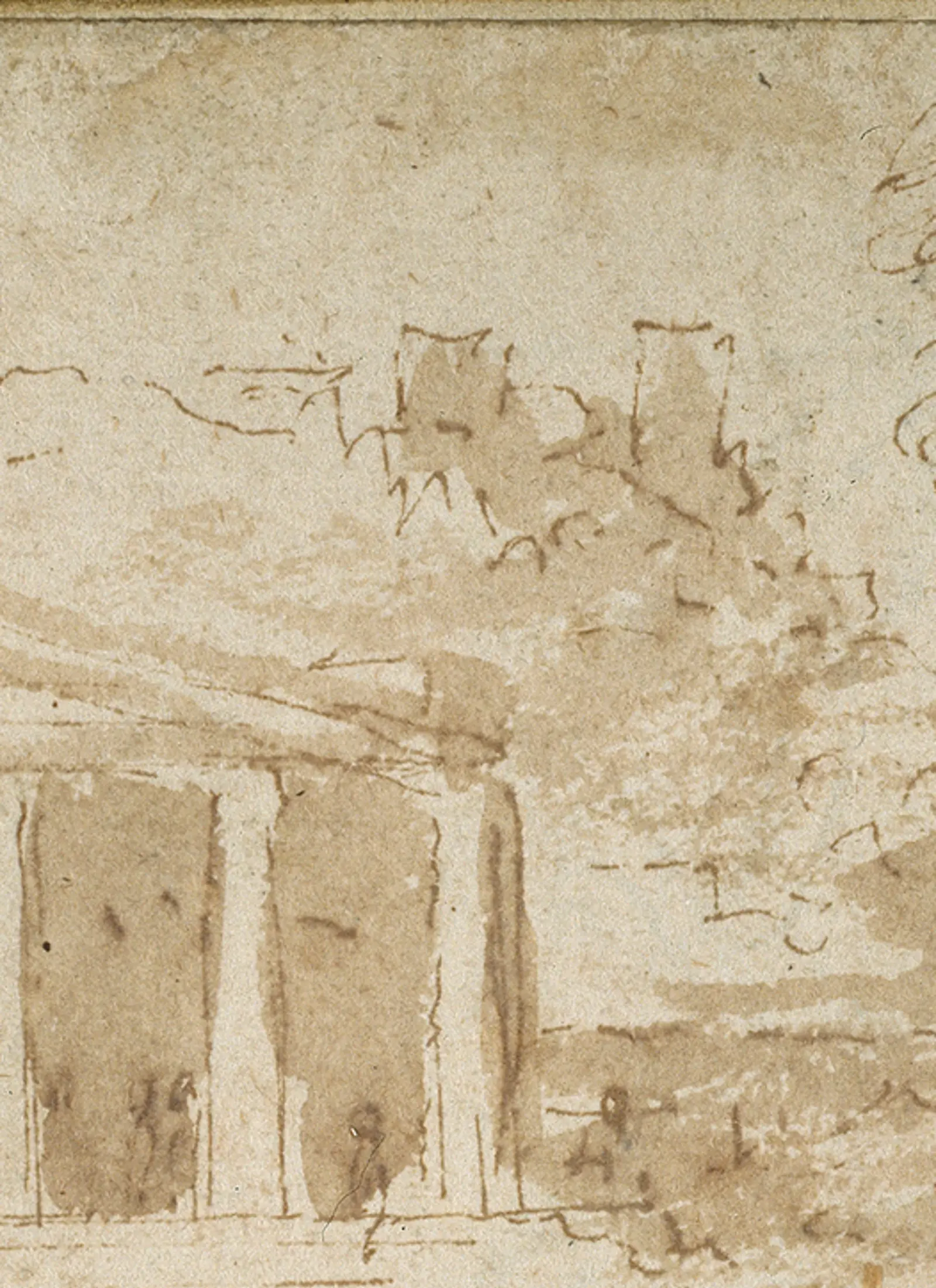

The architectural setting for this drawing is evident on the far left of the drawing where we seem to view two temples from different angles. On the middle left, and far more sketchily laid-in is a sequence of suggestive and faint lines on what looks like a distant hilltop. On the far right of the scene, the outline and arches of a building are visible. All of these structures, in varying positions, feature, in whole or in part, in one or both of Poussin’s paintings of this scene.

Look at this detail.

You’ll notice the solidity of the temple is suggested more by the wash indicating the vacuum of space between each column than by the linear outline of the temple itself. The work of contemporary artist Rachel Whiteread springs to mind.

We might think that drawing is a linear art form and that contour lines are vital, however, mark-making while drawing also depicts values or tones of light or dark (or contrasts of light and dark which is usually described as chiaroscuro).

In different periods (for example the Renaissance and Baroque) values might be rendered in different ways. Artists such as Filippino Lippi or Leonardo da Vinci may have used parallel hatching (among other things).

In this Poussin drawing, it really is all about the brown wash. By washing diluted ink across his surface, he has produced strong light and dark contrasts and built solid form at the same time.

All roads lead to Rome

Nicolas Poussin was a French painter yet he spent virtually all his working life in Rome. There, he specialised in history painting – scenes from the bible, mythology and ancient history. A subject such as this – the abduction of the Sabines – was typical of him.

He showed a talent for drawing at an early age and developed his draughtsmanship through studying anatomy, perspective and architecture in Paris.

Can you detect his skill in representing anatomy, perspective and architecture in this drawing?

In Paris, he discovered the Italian Renaissance through engravings. Aged about 30, he finally went to Rome where he stayed for the rest of his life (other than one trip to Paris 1640-1642).

Poussin’s palette was influenced by the colour of Venice. In Rome, he had access to antiquity and saw artwork of the Renaissance first hand.

As his own mature style developed, order and structure fused with a cooler colour palette. In his own writing he spoke of painting appealing to the mind and not the eye. He became known as a ‘painter-philosopher’. He developed a ‘theory of modes’ inspired by the modes of ancient music and proposing that every aspect of a painting should arouse an emotion in the viewer.

His late works are often described as classical and austere. He is largely credited for founding what is now known as the French classical tradition and in the late 19th and early 20th century, artists including Cézanne, Seurat and Picasso, admired the abstract formal design quality of his arrangement of structure and space.

Image: Nicolas Poussin, Arcadian Shepherds