This blog is part of a series penned during the exploration of the development and use of Chatsworth’s North Wing from its creation in the 1820s to today. Written by Lucy Brownson, PhD Research Student, it draws on the extensive archival material in the Devonshire Collections as well as studies of the spaces themselves.

In partnership with the White Rose College of Arts and Humanities (comprising the Universities of Sheffield and York, in this instance), ‘Remaking the North Wing’ comprises two interconnected PhD projects. Through this research we will unpick stories that illustrate how the 6th Duke’s North Wing has contributed to the life, work and identity of the house today.

The names Joseph and Sarah Paxton are well-known at Chatsworth. A self-made man who became a hugely successful landscape architect and gardener, Joseph came to Chatsworth in 1826, having met the 6th Duke of Devonshire while working as a gardener at Chiswick.

Though gardening wasn’t one of the Duke’s great passions, he liked this fresh-faced 23-year-old enough to hire him as Head Gardener at Chatsworth, and many of Paxton’s inventions are still central features of the garden today.

Countless visitors will have wandered through the Arboretum, peered at stone fruits growing in the Case, and gotten lost in the Maze, formerly the site of Paxton’s Great Conservatory. It’s at Chatsworth where Joseph met Sarah, who was the housekeeper’s niece. Sarah was also a pioneer in her own way, becoming de facto head of household and running the gardens whenever Joseph and the Duke were away on business. We know so much about Sarah’s pivotal role partly because of a 2019 AIM Biffa grant which enabled us to catalogue the Paxton Papers – some 2,000 letters to and from Joseph and Sarah, held in the Devonshire Collection Archives.

A name that many Chatsworth visitors probably aren’t familiar with, however, is Violet Markham – even though it’s largely down to her that the Paxton Papers found their way to the archives. Who was Violet Markham, and how did she end up with the Paxton Papers? What’s her own story?

As it happens, the answer to my first question is fairly straightforward: Violet Markham was Joseph and Sarah Paxton’s granddaughter, as her mother Rosa was one of the Paxtons’ eight children.

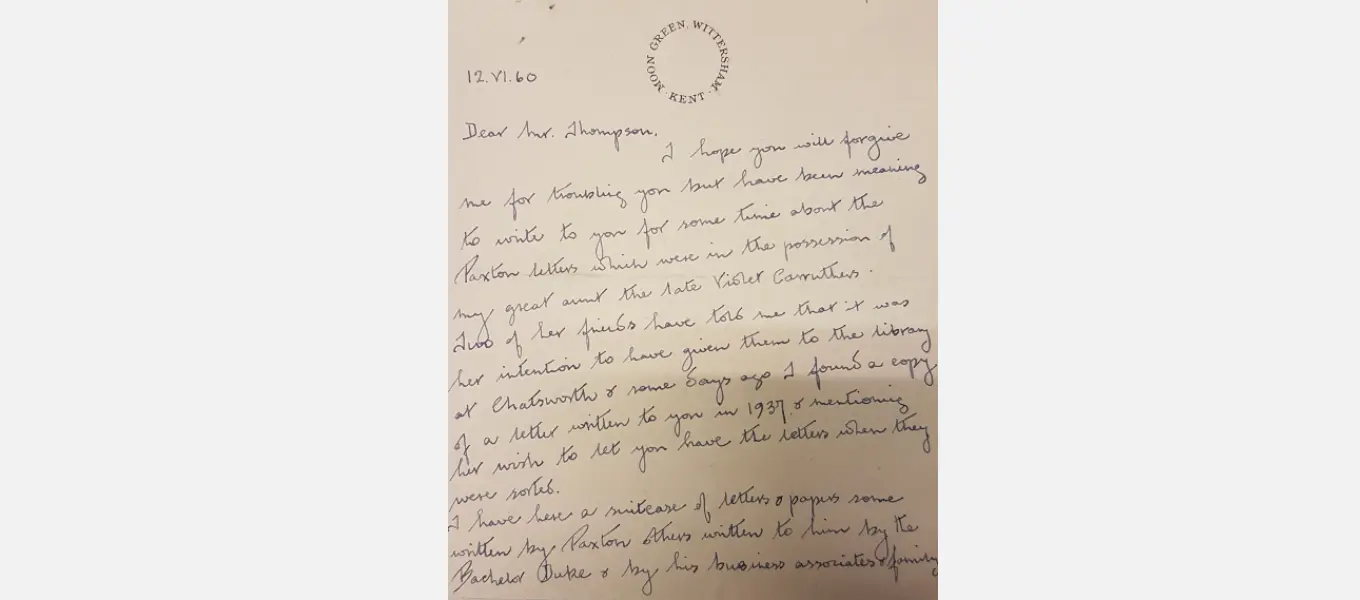

There’s a slim bundle of letters in the Archives here between one of Violet’s descendants and Francis Thompson, the former Librarian to the Duke, many of which discuss the fact that she promised the Paxtons’ correspondence to Chatsworth as early as the 1930s.

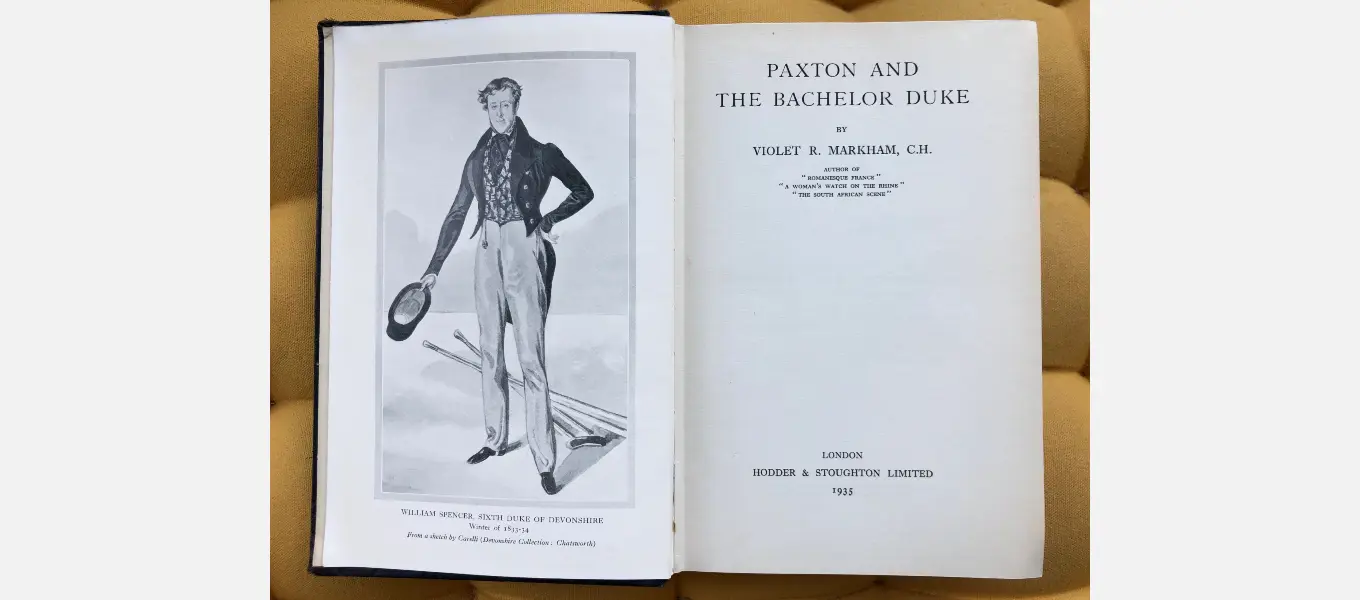

In her own lifetime, the Paxton Papers formed the source material for Paxton and the Bachelor Duke, her 1935 biography of her grandfather’s friendship with the 6th Duke. It’s thanks to Markham’s meticulous safekeeping of her grandparents’ papers that they survived and were eventually given to Chatsworth in the 1960s. These letters now form an important collection that speaks not only to garden and architectural history, but also to social history and the experience of being a Chatsworth estate worker in the nineteenth century.

So that’s that, right? Well, not exactly. As I discovered when I began researching Violet Markham, she herself was a remarkable, and undeniably problematic, person.

Born in 1872 to a wealthy colliery-owning family, Markham is remembered as a social reformer and a vocal anti-suffrage campaigner. This seems like a contradiction in terms – especially when we consider the fact that in 1927, she made history by becoming the first ever female mayor of her hometown of Chesterfield, a huge achievement in an era that offered women almost no political representation.

Despite her opposition to women’s suffrage, Markham was good friends with many lifelong suffragists and social reformers – the writer and women’s suffrage campaigner Mary Stocks once described her as ‘the best feminist I’ve ever known’. As an affluent Liberal social reformer herself, Markham enacted a lot of social good, including running canteens for the poor, establishing a school and an educational trust, and helping to alleviate poverty through her work for the Unemployment Assistance Board and the National Relief Fund.

It would, however, be disingenuous to gloss over the less palatable parts of Markham’s life in order to portray her as some kind of feminist pioneer, and here’s why: history doesn’t work that way. History is messy and multifaceted, not a grand, linear storyline.

As a contemporary researcher, it’s my job to explore the many threads that make up the lives and worlds of the people I research – without tucking away the more troubling ones.

With that said, Violet Markham’s political work is best understood in the context of late-19th and early-20th century British imperialism, which she passionately supported.

Having grown up in a lively, intellectual house, Markham first became engaged in imperialist politics through her travels to Egypt and South Africa in the 1890s, both of which were under British colonial rule. She quickly got caught up in imperial political tensions in South Africa and became a passionate supporter of the British colonial administrator Alfred Milner, one of the British instigators of the Second Anglo-Boer War.

Milner was a staunch white supremacist who believed in British paramountcy above all else; his vision (which Markham supported) was one of white nationalism and continued colonial rule in South Africa. During and after the conflict, Markham herself worked as an imperial propagandist for publications including the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, and she often expressed deeply offensive, racist views in her own writing.

Much of Markham’s involvement in domestic politics was also rooted in patrimonial and imperialist ideas of philanthropy. As recent events have highlighted, Britain’s relationship with philanthropy is freighted with tensions and historically, many so-called ‘philanthropists’ were responsible for or in support of colonial violence. Markham’s imperialist politics went hand-in-hand with her strong opposition to British women’s suffrage: one of her main objections to women gaining the vote and getting involved with parliamentary politics was that women weren’t experienced or knowledgeable enough to lead the British Empire.

Throughout the early 1900s, Markham actively rallied against women’s suffrage through her involvement with National League for Opposing Woman Suffrage. In February 1912, addressing a packed Royal Albert Hall at a League meeting, Markham stated that ‘the majority of women did not want the vote, but it was not a question of what they wanted.’ Even though she was a vocal political commentator, Markham often undermined her own position in order to deprive other women of the same opportunities; clearly, she set herself apart from the majority of women.

I’ll level with you, reader: Violet Markham led me down something of a research rabbit-hole. Working from home for the last five months, without easy access to the Archives, I’ve tumbled headfirst down a fair few of them.

My research focuses on women’s contributions to archival practices at Chatsworth, and – albeit indirectly – Violet Markham is one of these women. Most of the papers we hold relating to Markham herself speak to her custodianship of the Paxton Papers and her cordial (if infrequent) relationship with the 9th Duke, Victor Cavendish, and Duchess Evelyn; they don’t offer us much insight into Markham’s own life and work.

In this way, then, a peripheral character like Violet Markham can speak volumes about the gaps and absences in the archive; it exposes how an archive, any archive, can only ever contain fragments of a life.

Researching Violet Markham also made me pause to consider how the legacy of British colonialism and imperialism is always there in the archives; it’s in the records themselves, in their past and present lives.

As many across the heritage sector commit to an ongoing journey of learning and unlearning our histories, we can’t keep presenting the same neat-and-tidy stories of political and social pioneers. Paying attention to the footnotes – asking how and why collections like the Paxton Papers exist in the present – often brings us face-to-face with the unseen people and histories connected to these archival fragments, however challenging that may be.

Read about The Devonshire Group's ongoing academic research into archival links with colonialism on the Devonshire Group website.

Learn more about Lucy's research here.

This blog draws from an article by Eliza Riedi for Albion journal, entitled ‘Options for an Imperialist Woman: The Case of Violet Markham’ (2000).

The Devonshire Collection Archives identifier for the Paxton Papers is P – find out more about the collection, and other family papers, here.