We use platforms such as YouTube and Vimeo to display videos. These require the use of cookies, for which we need your consent. To watch this video, please click here to allow cookies.

Prefer to listen? Play the film to hear author Louise Calf read this blog aloud.

You might think that having the research remit of just one room at Chatsworth - namely the Theatre - would provide a researcher with clear research boundaries that limit said research to the four walls of said room. If you think this, you are misguided. However, for the last 7 months this researcher has been getting to grips with exactly this: how and why were the walls of this room built?

Gloriously, asking this question takes us all the way back to the building that was on the same site the current north wing occupies today: Paine's old north wing. It can be a stretch of the imagination to picture a building that no longer exists. For this reason, let's start with the only known image we have of it, taken from the sketchbook of Sir Jeffry Wyatville, the architect responsible for replacing it with the pale, honey-coloured building we see today. Wyatville's sketch is a gift of a record, revealing so much more than might at first meet the eye. Have a good look.

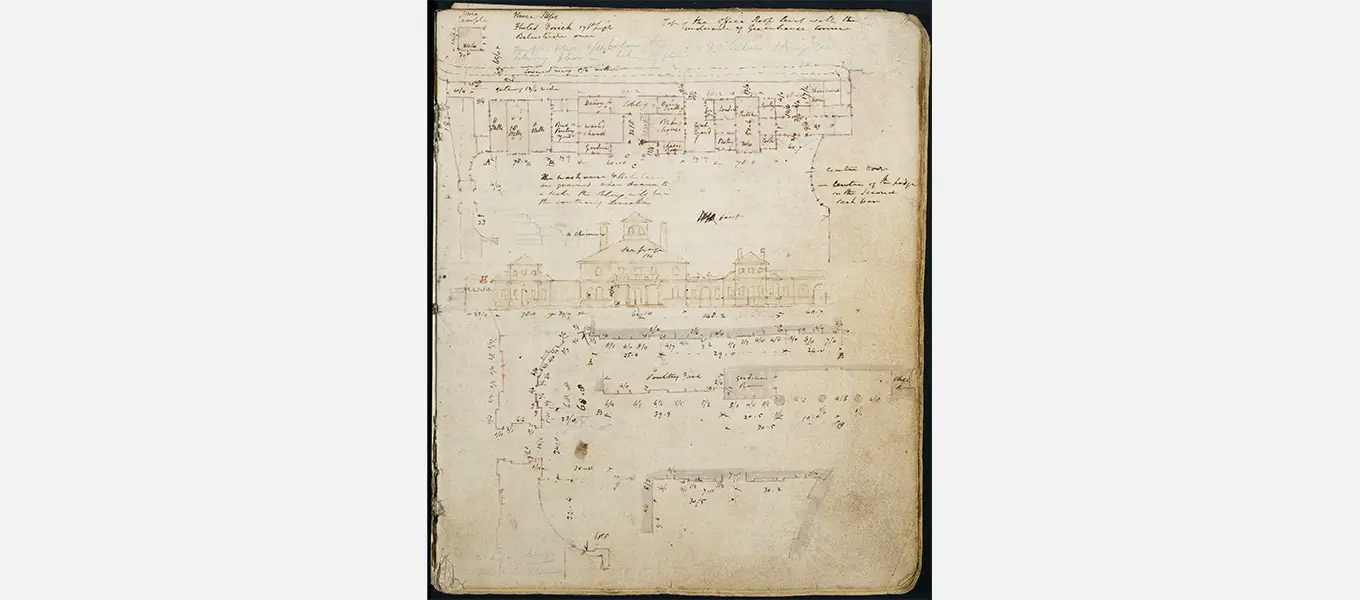

A scan of a page from Wyatville’s sketchbook with the only known image of Paine’s north wing. (Devonshire Collections Archive reference WY/T/1)

The old north wing, along with the stable block, two beautiful bridges and the mill, was designed by James Paine in the middle of the 18th-century for the 4th Duke of Devonshire. My knowledge of Chatsworth in this period is thin, to say the least, so let's not dwell here but focus in on the drawing itself and what it tells us. Wyatville has shown the wing in both plan and elevation form - so, from a bird's eye view looking down at the ground floor, as though slicing the building horizontally, and stood looking all along one façade of it. These choices are interesting in themselves: while they're both established ways to show how a building fits together, they're not comprehensive records of the building, so Wyatville is already making certain editorial decisions - we'll come back to this in a minute. The plan form is annotated with the names of each room, or the uses to which those spaces are put, presumably so he knows what functions still need to be accommodated in the changes he's about to make. Meanwhile the elevation is only of the intended 'front' of the building - the side you would see if you were a guest to the house, approaching the entrance in the north sub-hall, as a visitor would today. The more we look at these sketches, the more intriguing this becomes.

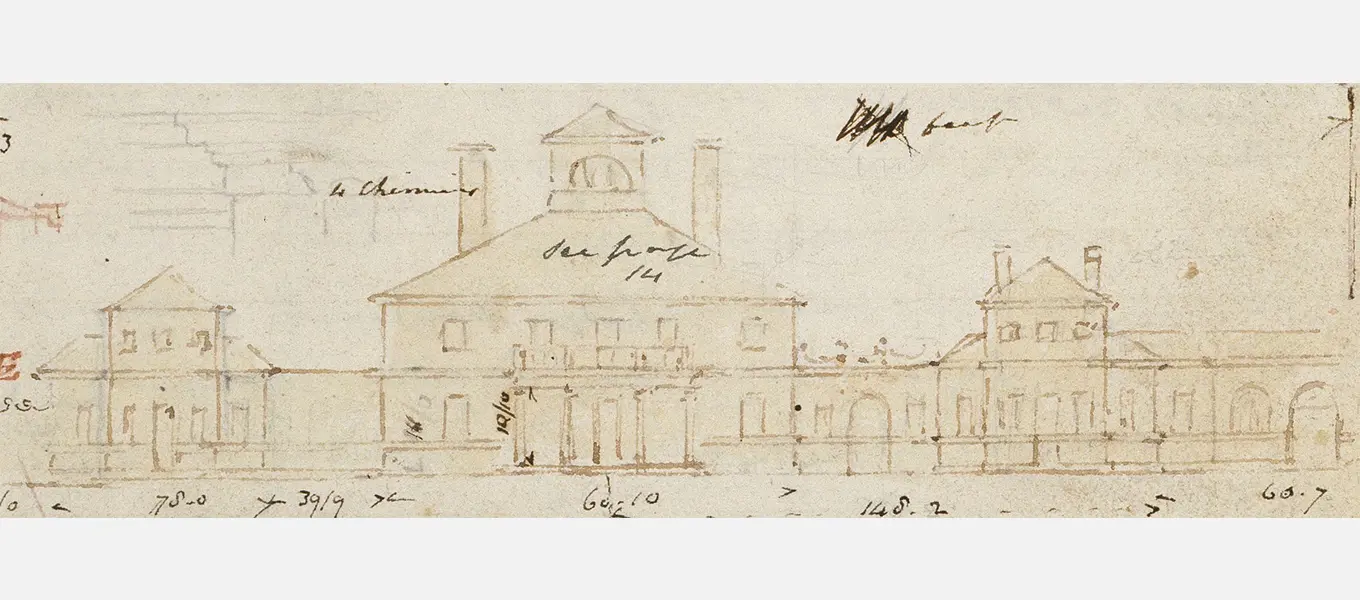

Wyatville’s elevation sketch of Paine’s north wing.

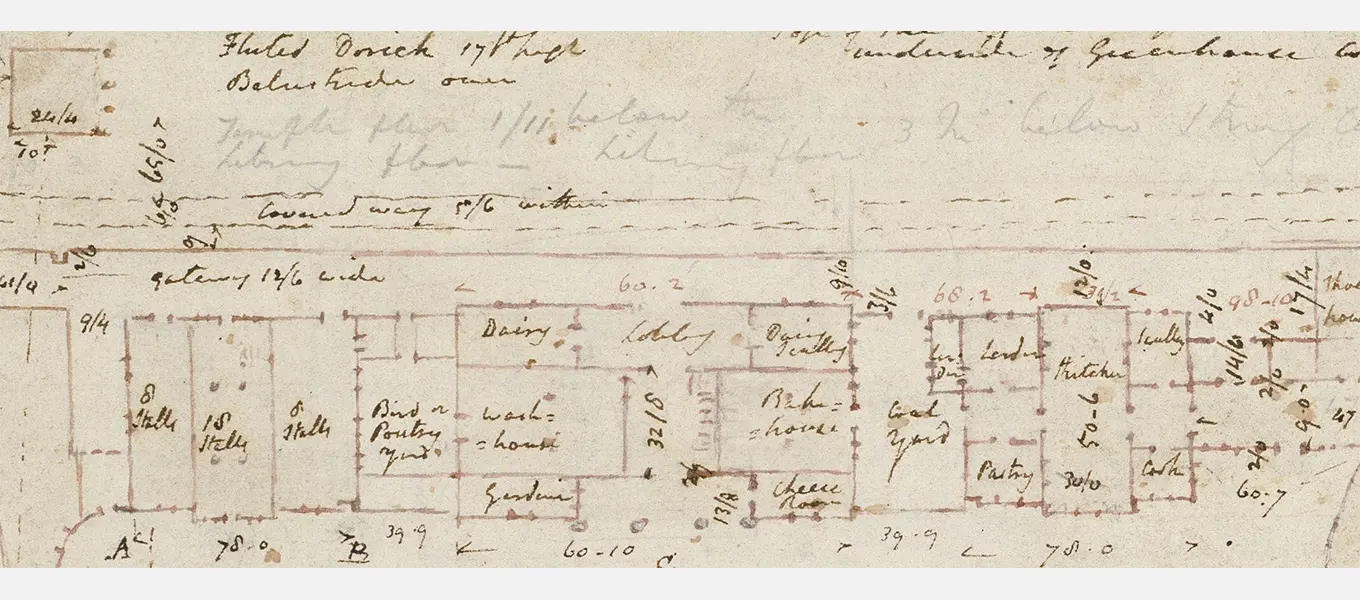

Wyatville’s plan sketch of Paine’s north wing.

The elevation - the 'front' - of Paine's north wing shows three pavilions with connecting walls, more closely resembling residential villas than the working spaces the plan form reveals them to be. Reading Wyatville's handwriting on the plan, we can start to imagine what life in this old wing might have been like. On the very right hand side, the south end - or the end closest to the main house - Wyatville identifies the Kitchen. This was moved here when the sub-hall became an entrance, and it's easy to imagine why keeping the kitchen as near to the dining areas as possible would be desirable. In the same pavilion are the Scullery, two Larders, a room for Pastry and what looks to be an office for the Cook (though if you read something else, do let me know). Moving north, along to the left - away from the house - we pass through the Coal Yard, surely a grubby area and presumably open to the sky. And then we reach the central pavilion, which contains the Bake House, the Cheese Room, the Dairy and Dairy Scullery, and Wash House. Moving along again to the north, and we're in the Bird or Poultry Yard before we finally reach the stable block, housing a total of 34 stables.

So, it's fairly safe to deduce that this is a place of human and animal activity, all serving the daily needs of the various groups of people who used the house, needs from eating to washing to transportation. Imagining these activities can summon sounds, smells and sensations in our minds: from the clucking and scratching of chickens in the poultry yard, to the smell and creak of leather harnesses in the stables with the horses stamping their hooves on a floor strewn with straw, to the humid heat of the wash house, the smells of cooking from the kitchen.

The more we look at this plan, the more we notice the doorways marked on it, and the more we observe that most of these working spaces are accessed from the 'rear' of the pavilions. Can you see the long yard running 'behind' the wing? Do you see Wyatville's note of the 'gateway' on the very left hand - or north - side? Look again at the elevation drawing. Wyatville appears to have included a line through the arch between the central and right hand pavilion. It may simply be the draughtsman's license, but this could also indicate that this is a wall: a blank, filled arch with a string course of stone running across it. With all this in mind, when you imagine all the noise and activity of the people and animals moving through and around these rooms, do you start to question which is actually the 'front' of this block? If you're someone who's more likely to be working in a house like Chatsworth, rather than visiting as a guest, which side of this wing are you likely to see more of?

Of course, we know that both Wyatville and Paine were working for the Dukes; that their clients were those people who would be visiting the house, rather than working in it; we may also be familiar with phrases such as 'service yards' or 'servants' entrance', but it's worth interrogating this familiarity in light of what Wyatville has chosen to record here. What does it tell us that Paine designed a wing that would not only hide, but actively disguise the very activities of a house on which it depends for its smooth running? What is to be gained by this illusion, and by whom? A false notion of country house life as one of luxury and concomitant ease? Whose ease? Or is it the stone and mortar manifestation of a division between the leisure and working classes that occupy a country house estate? If you worked here, taking care of the horses, or washing sheets and linen, would this emphasis mean anything to you?

As you'll know if you've visited Chatsworth, the whole site is on a hill. The wall that runs on the other side of the long service yard marks the boundary of the garden beyond and, on Wyatville's drawing, you can see a long covered way leading through it and past Flora's temple. Paintings suggest shrubbery between this covered walkway and the boundary wall so that, from the garden, looking west towards Paine's wing, the whole thing would not only be sunk on a lower level, but it would also be obscured by trees and bushes. Perhaps the rooftops would be on view, particularly that of the central pavilion, but the activity of this wing would again be tucked away out of sight.

All of this, to my mind, is fascinating when you consider what the 6th Duke and Wyatville then did to change it all, not only retaining these essential household functions but also introducing grand new entertainment spaces and both staff and guest accommodation. And all on a scale and magnificence that consciously drew attention to itself. With the activities of both staff and visiting guests contained within the same exalted building, the divisions between the two become far less distinct: they are pretty much happening cheek by jowl. As you'll still see today if you join a behind-the-scenes tour, the offices and staff rooms run just behind, beneath or above the extravagant front-of-house spaces, often with only a wall to separate them.

Despite these huge architectural and social differences between the old and new north wings, Wyatville's building owes far more to its predecessor than is at first apparent, particularly when it comes to my focus of enquiry: the Theatre Tower. But that's a thought for another day...

Wyatville's design for the West Front.