This monthly blog series delves into the development and use of Chatsworth’s North Wing from the early 19th century to the present day. ‘Remaking the North Wing’ comprises two interconnected PhD studentships: one on the history of the Victorian theatre, and one on the development of the Devonshire Collection Archives. In this blog, PhD student Lucy Brownson introduces her project, ‘Archive as Practice, Space & Identity at Chatsworth’.

At the heart of Chatsworth’s rich and illustrious history is the Devonshire Collection Archives: over 6,500 boxes of historic records that inform everything we know about life and work across the estate over the last 450 years. As a doctoral researcher in my first year of a collaborative PhD between Chatsworth and The University of Sheffield, I research the history of the archives – namely how they came together, and the lives and labours that have been central to their formation. I like to think of my work as tracing the history of – well – history! As a feminist researcher and an archivist by training, I’m especially interested in how women, through documenting their own lives, work, and the worlds they moved through, have shaped Chatsworth’s archival collections and the stories we tell about the house today.

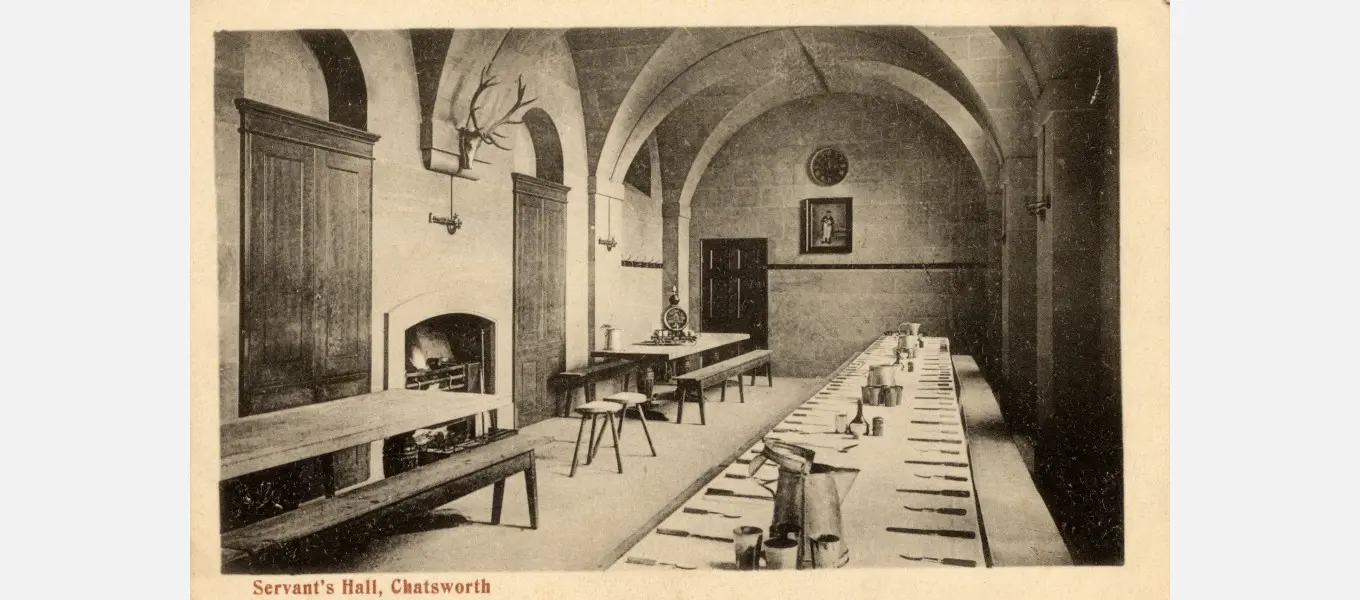

Much like our main archive store, the former Servants’ Hall tucked away in the house’s North Wing (above), many of these women’s lives and contributions to Chatsworth’s history aren’t immediately visible. We know that William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858) made substantial additions to the private library at Chatsworth, for example – but what do we know about his great-niece, Lady Louisa Egerton (1835-1907; pictured below), who played a major role in cataloguing his extensive book collection?

Well, comparatively little. Louisa was the only daughter of William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire and Blanche Cavendish, Countess of Burlington (1812-1840); her brother was Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire (1833-1908). Although she married into the Egerton family, Louisa spent a great deal of time at Chatsworth throughout her life and indeed, she played a major part in managing and developing the Devonshire Collections and Cavendish cultural capital. All the same, Louisa is only referenced in passing (if at all) in many published biographies of Chatsworth and the Cavendish family, even though swathes of her letters in the archives speak to her efforts to properly care for the family’s collections, from rare books to priceless artworks. Writing to her father William in 1874, Louisa reports that she has invited a British Museum curator to check the condition of some of the Old Master Drawings at Chatsworth. She writes:

‘[The curator] is dreadfully distrest about the Drawings in the Sketch Gallery, & I fear with reason – they certainly have faded very much, as one can see…’

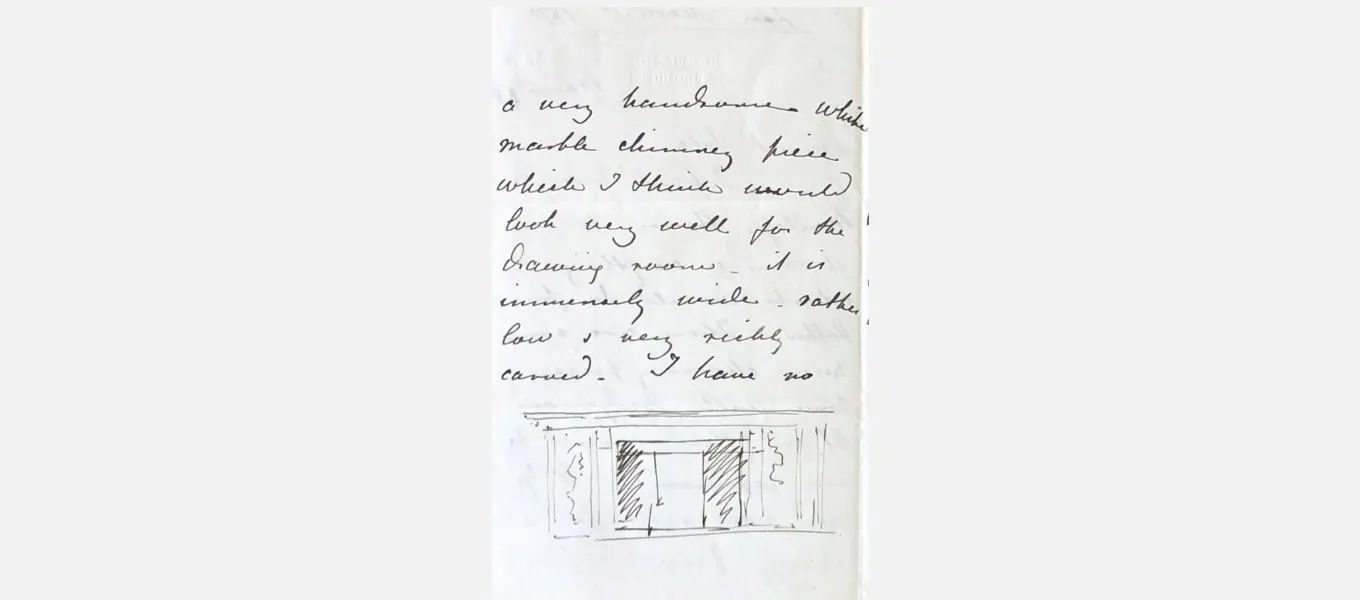

Louisa suggests fitting filtered curtains on the windows to protect the paintings from light damage, a preventive conservation measure which many visitors to Chatsworth may well have seen around the house today. She goes on to say that she intends to get some protective cases for etchings and prints at Chatsworth, adding that she’s already procured a case from the British Museum. Elsewhere in her letters, Louisa liaises with art historians and heritage experts about how best to safeguard the family’s collections, as well as utilising her artistic talents to design archival storage units, bookcases, fine art frames and furniture fittings – below is her sketch of a marble chimneypiece purchased for her childhood home of Holker Hall, enclosed in another letter to her father. If it weren’t for Lady Louisa Egerton’s proactive approach to conservation and archival preservation at a time when these weren’t central priorities as they are at Chatsworth today, we may not be able to enjoy and study many of the Devonshire Collection’s crowning glories. Louisa’s collections care has greatly enriched the house’s history and its cultural life; I hope that by tracing her life and work, I can help to place her back in the frame and give her due credit.

Over the coming months, I’ll return to this blog to explore other individuals whose lives and work have fundamentally shaped the archives, collecting practices, and the history of Chatsworth itself. Although I’m missing the house (especially my morning walks through the parkland – pictured below) in this period of working from home, the wonders of digitisation and the hard work of Chatsworth’s incredible Collections & Exhibitions department enable me to continue my research remotely until we can all safely return to work again. In the meantime, I’m looking forward to sharing archive stories and new discoveries from the safety of my sunny kitchen table – I hope you’ll enjoy them, too.