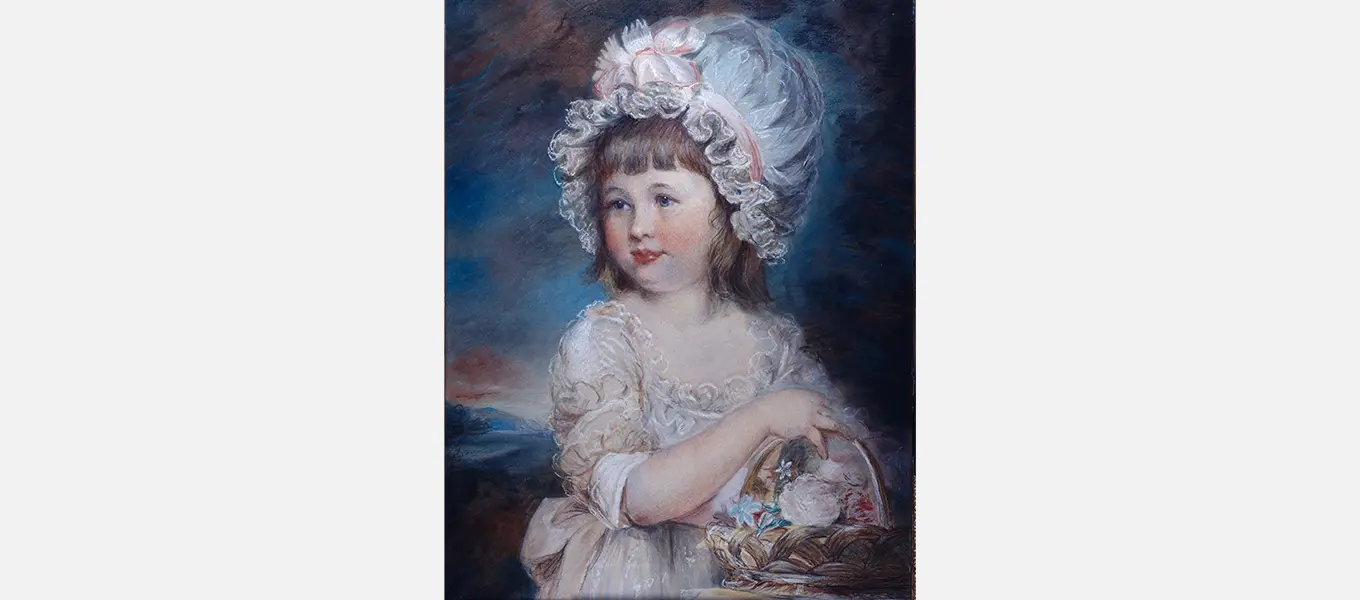

Lady Georgiana and Lady Harriet, daughters of Duchess Georgiana, were like their mother in many ways. Their love of clothes filled their letters and there was always an upcoming occasion which required a new outfit. For two young girls, the preparations that went into balls and the anticipation of what to wear was far more exciting than any of the lessons they were meant to doing, much to the annoyance of their governess. The children were well aware that their interest in clothes was not shared by everyone but could not help themselves. When writing to Selina, their governess, the twelve year old Georgiana told her ‘I know you don’t care much for how we were dressed but I will just say we were in pink & silver & silver ribbons in our heads’.

The girls took great pride in their outfits and it was only natural that their interest in appearance would extend to what those around them wore. With their own set of servants in the nursery, including a nurse, nursery maid and a governess, the children had constant company who would have acted as their companions when they ventured outside of the house. When out exploring the children were keen to show off their nursery servants to the rest of the world and how they were dressed played a crucial role.

From a young age, the children spotted differences between the way they dressed and the way their servants dressed, even if they did not understand the reason why. At the age of six, Lady Georgiana noticed that her governess did not wear diamonds and wondered why not. Writing to the Duchess, Selina told her that whenever she went out, Lady Georgiana ‘wants me to be the best drest’ and had even suggested that wearing a bit of rouge ‘wou’d be a great improvement’.

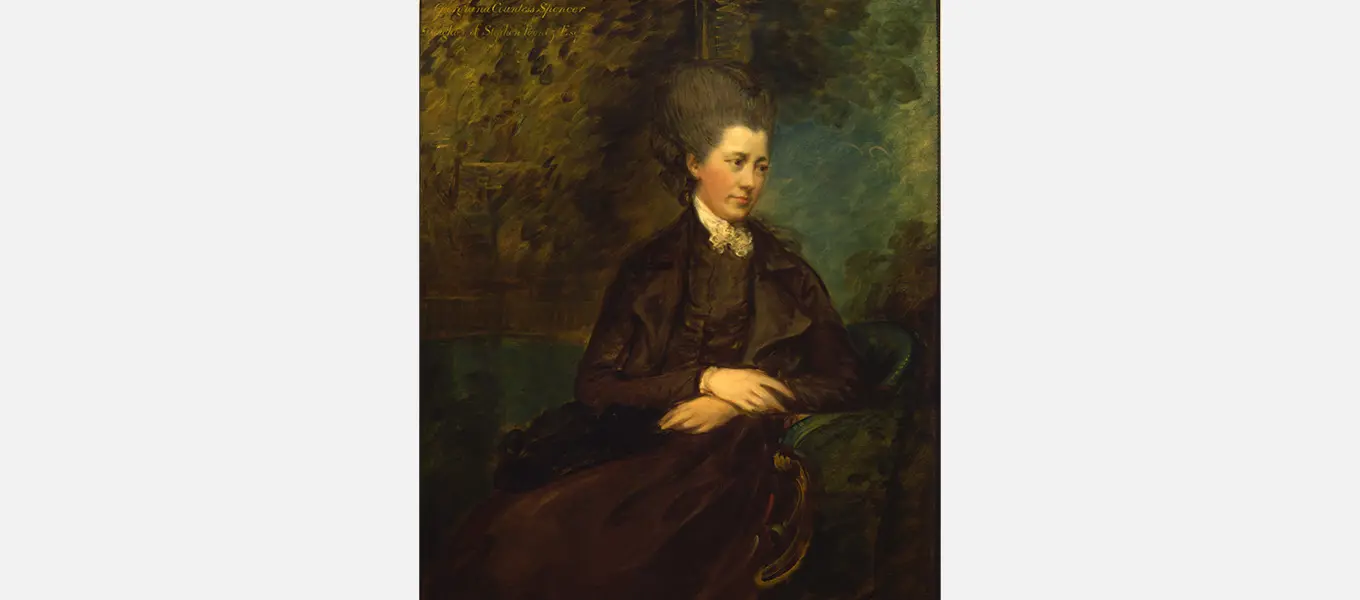

The issue of what servants wore was a topic often debated by employers and social commentators. If a servant was too fashionably dressed they might be mistaken for their master or mistress, while dressing in an outdated style would fail to reflect the status of their employer. While some male servants at Chatsworth received a livery paid for by the Duke, female servants had to provide their own clothing. Daniel Defoe lamented the lack of livery for female servants and argued that servants should dress to fit their station in order that ‘we may know the mistress from the maid’.

Worry only increased towards the end of the eighteenth century when the growing fashion for printed cotton dresses replaced the desire for sumptuous silk fabrics. Not that the fashionable Duchess Georgiana appeared to mind what her servants wore, or at least not those who were in important roles like the governess. In 1789 while in France, she had even bought Selina a watch which had cost her 8 guineas, nearly £1000 in today’s money. In fact, the Duchess seemed to encourage Selina to dress well and acknowledged that ‘she likes & always is very well drest’. The Duchess joked to her mother, Countess Spencer, she hoped Selina had not been influenced by the Countess’s ‘dowdy’ style after spending so much time with her.

Although we do not know exactly what Selina wore, it appeared she had more freedom than many other servants to choose her wardrobe. Her annual wage of £100 would also have helped her purchase styles others could only dream of. Crucially however, Selina’s role as governess meant she made sure the Cavendish children were well educated and not only very well dressed.