Prefer to listen? Play the film or the audio file to hear author Frankie Drummond Charig read this blog aloud.

We use platforms such as YouTube and Vimeo to display videos. These require the use of cookies, for which we need your consent. To watch this video, please click here to allow cookies.

Dorothy Boyle’s life has too often been treated incompletely (perhaps even unfairly) in historic literature - if she has been remembered at all. Born Dorothy Savile in 1699 – to Mary Finch and William Savile, 2nd Marquess of Halifax – it was her marriage to Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington in 1721 that gave her the title Lady Burlington. Her connection to Chatsworth is through her son-in-law William Cavendish (1720 – 1764) who married Lady Burlington’s daughter Charlotte Boyle, and became heir to the Burlington estates after Charlotte’s death.

It could be argued it was Lady Burlington’s marriage that was crucial to developing her creativity and patronage of the arts, but it is also possibly a contributing factor to her treatment as a passing footnote or indeed an omission altogether from the history books.

After Godfrey Kneller, Richard Boyle (1695–1753), 3rd Earl of Burlington, © York Art Gallery

Lord Burlington, the ‘Apollo of the arts’ as Horace Walpole called him, was an architect and primary patron of William Kent.¹

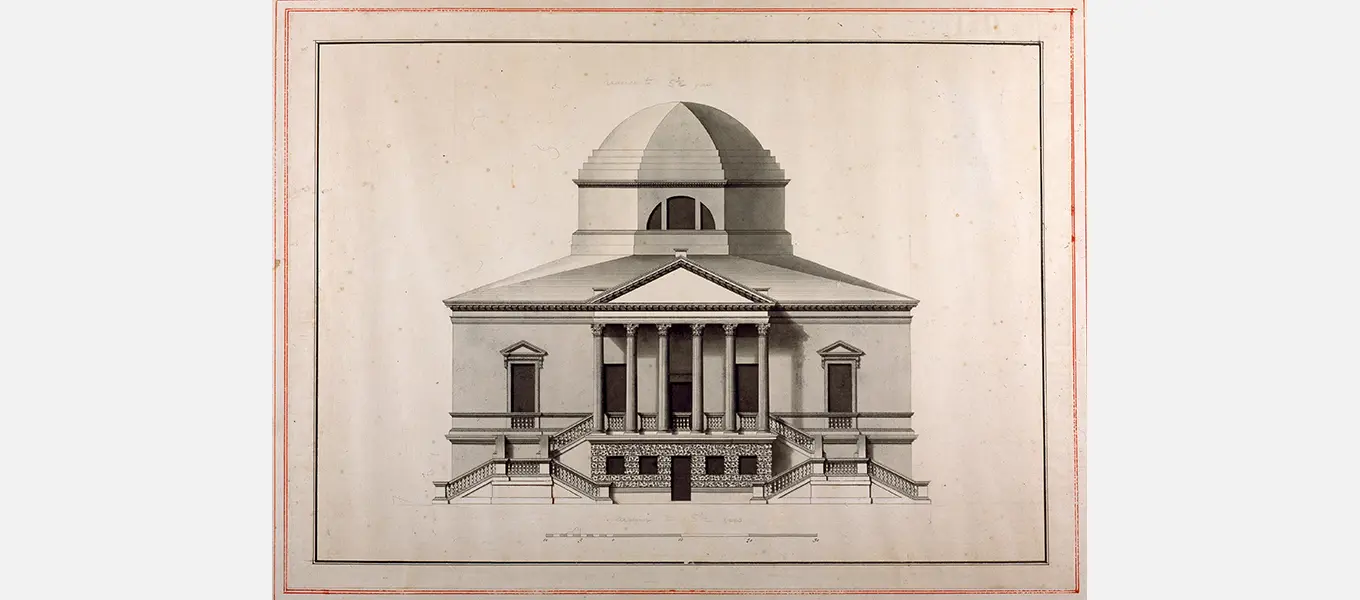

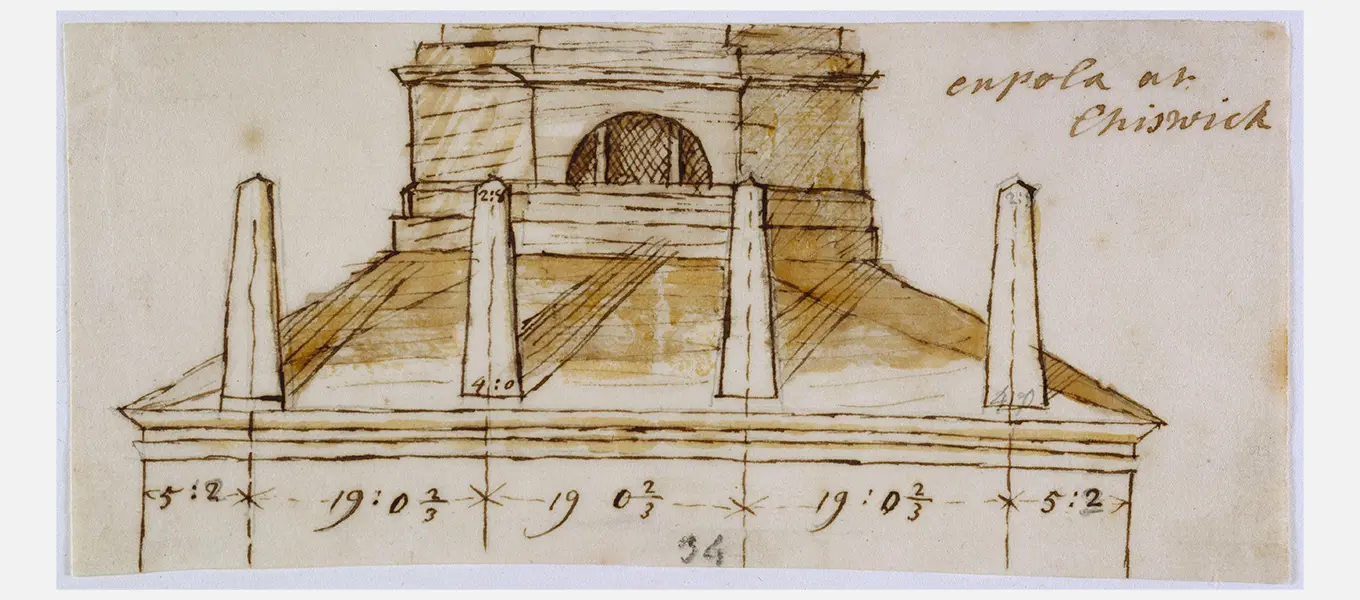

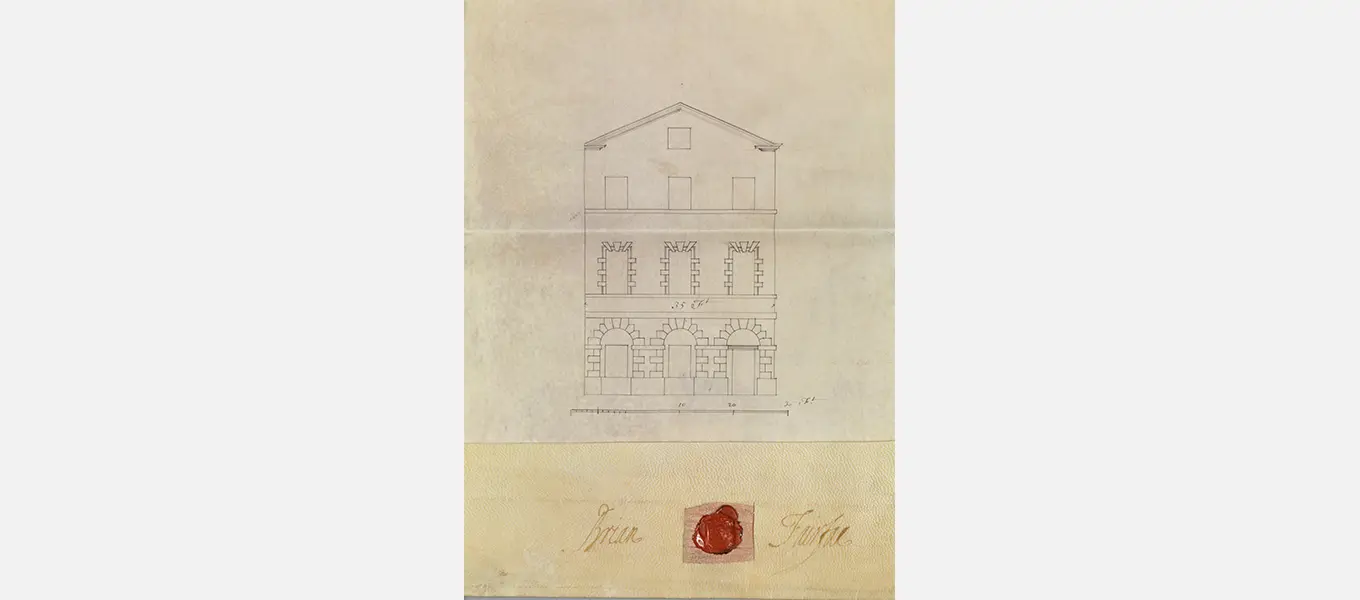

Lord Burlington's design for Chiswick (Flitcroft Boyle 8 12)

Burlington’s architectural designs and Kent’s interiors for the villa at Chiswick were ‘a manifesto of Palladian perfection’. Lord Burlington’s name is synonymous with the national establishment of Palladian architecture in the 18th century.

Mark De Novellis in his unique study of Lady Burlington as an artist, points out that in explorations of Lord Burlington and his circle, Lady Burlington has been ‘presented as his [Lord B’s] comic counterpart, his antithesis brimming over with excess and irrationality and violent passions’.²

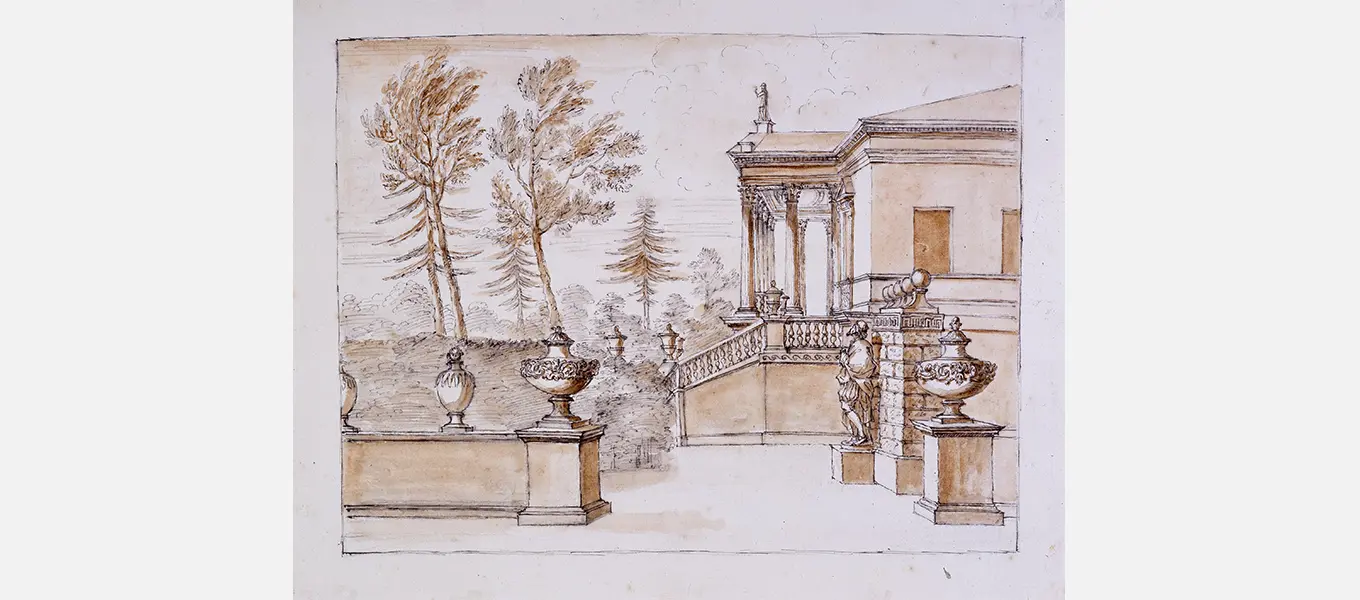

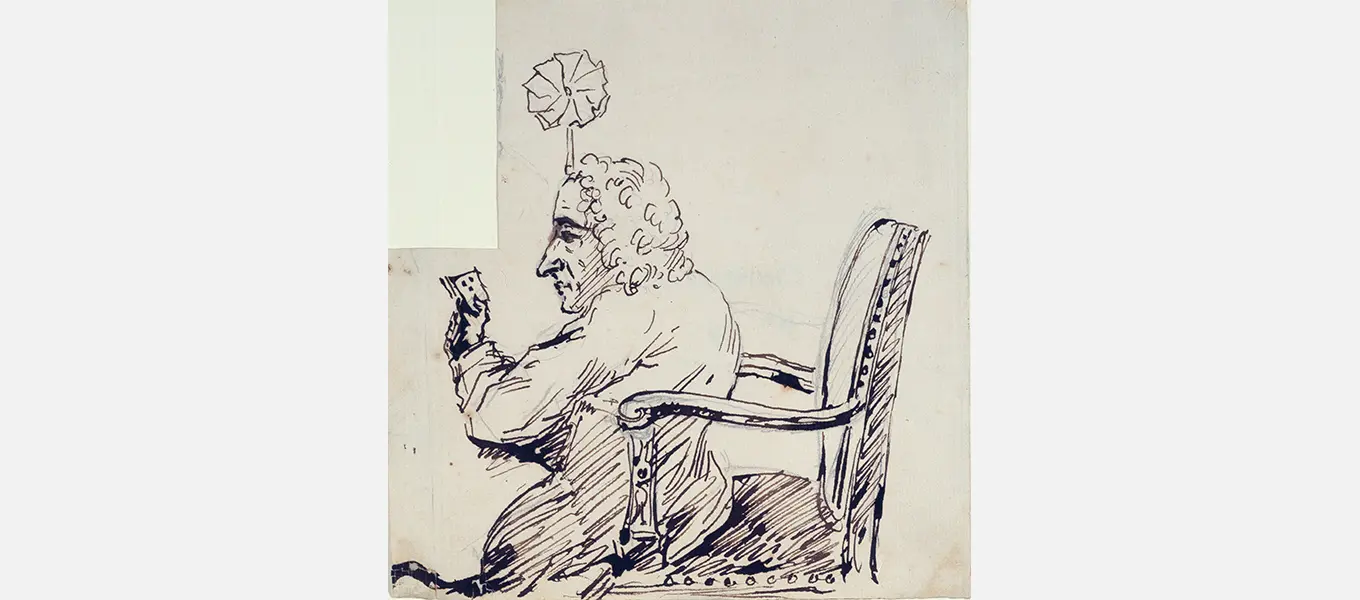

William Kent's sketch of Chiswick (26A 13)

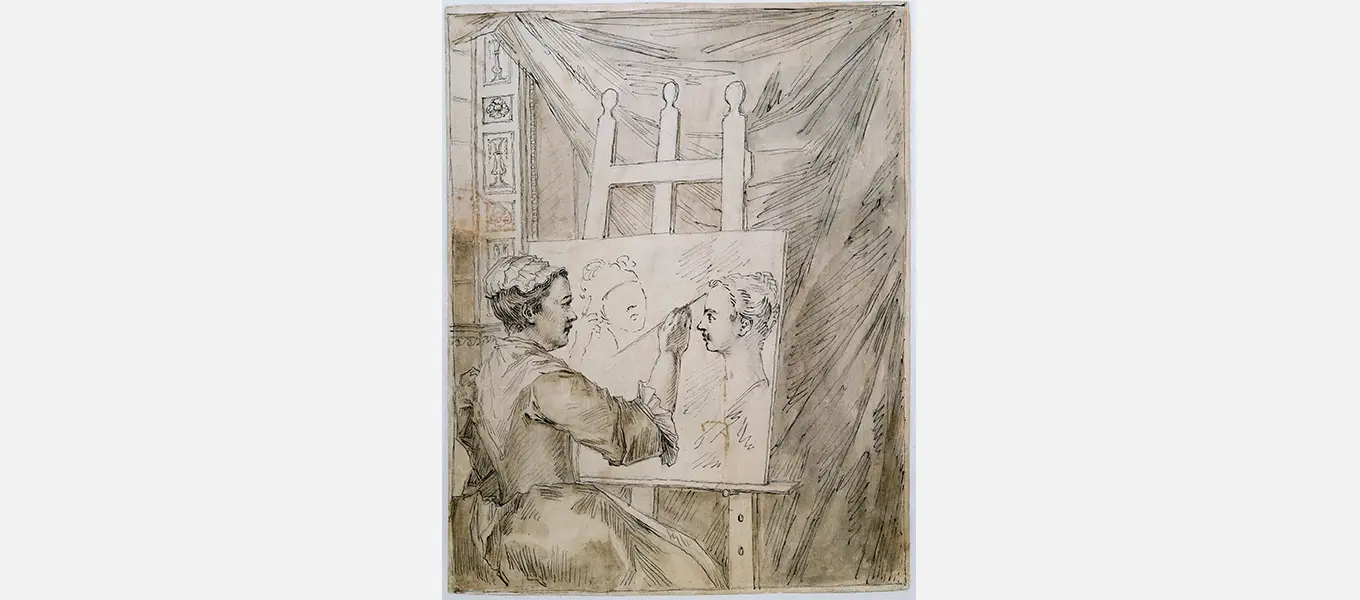

William Kent's sketch of Lady Burlington painting (26 79a)

Yet little or no mention is made of her role in cultivating their circle of artists, actors, royalty, politicians and noblemen. And certainly her own oeuvre and status as an artist in her own right has only recently begun to be examined in earnest.³ This omission is stark when one considers the amount of correspondence that remains at Chatsworth, thanks to Lady Burlington and her connections. A point to be considered further shortly.

Firstly however, let us consider life before Lord Burlington. After the death of her parents, Lady Dorothy Savile as she was, went to live with her grandfather Daniel Finch, 2nd Earl of Nottingham, 7th Earl of Winchilsea, at Burley in 1718.

With an inheritance of £30,000 and an annual income of £1,600 Lady Dorothy was, in the words of the Duchess of Marlborough, “so desirable that everybody is fighting for the prize”.⁴ In the archives at Chatsworth there are letters relating to one of these admirers – Scroop Egerton, 4th Earl of Bridgewater, and later 1st Duke. From the letters that exist it is clear that Lord Bridgewater’s proposal and advances had been ignored by Lady Dorothy.

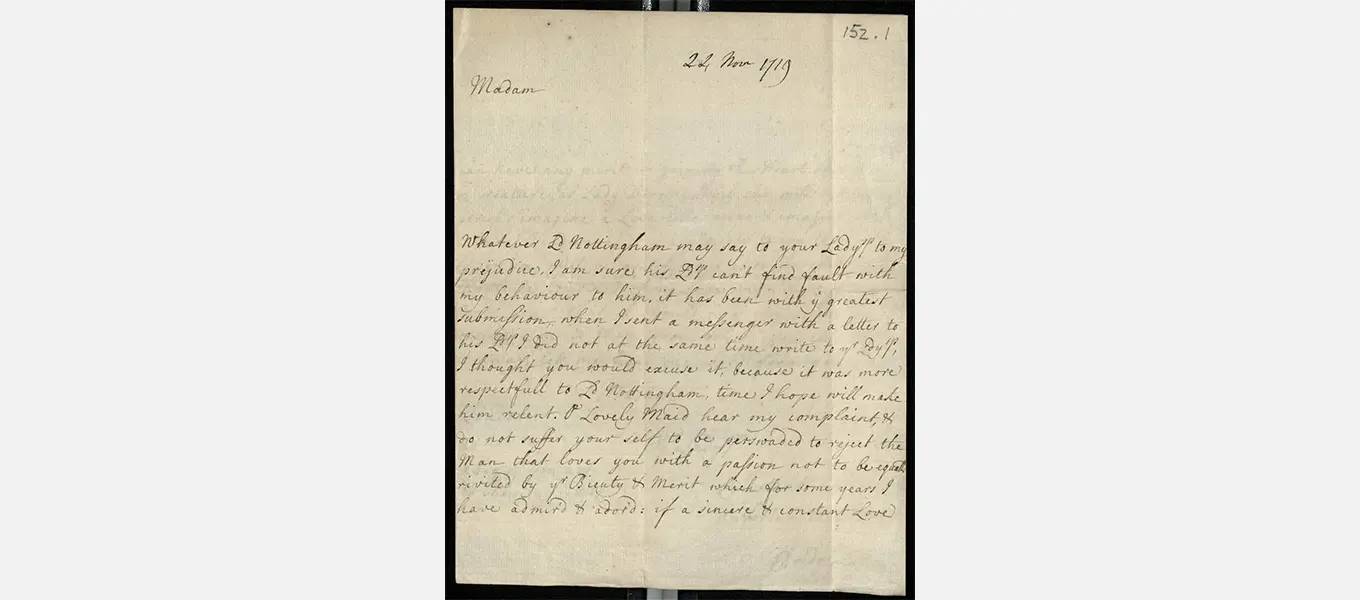

Lord Bridgewater's letter to Lady Dorothy, 24 November 1719 (CS1/152.1)

On 24 November 1719, he writes: “O lovely maid hear my complaint, and do not suffer yourself to be persuaded to reject the man that loves you with a passion not to be equalled, riveted by your beauty and merit which for some years I have admired and adored, if a sincere and constant love can have any merit in gaining the heart of so charming a creature as Lady Dorothy Savile she will not let me perish; imagine a love like mine and imagine what torment I endure….”⁵

Charles Jervas, Scroop Egerton, 4th Earl of Bridgewater (Later 1st Duke of Bridgewater), c.1710

He pursued Lady Dorothy for over a year and initially went to Lord Nottingham about marrying Lady Dorothy, which clearly unimpressed Lady Dorothy, who at the age of twenty was showing her confident, decisive and self-assured nature. Many women her age would already have been married, however, Lady Dorothy clearly was not willing to compromise in her choice of partner and it was a decision her grandfather was willing to leave to her, within reason. In his letters, Lord Bridgewater tries to persuade her that her grandfather believes she ought to acquiesce to the proposal, but later he mentions that he is perturbed to find she has banned her grandfather from talking to her about Lord Bridgewater at all.

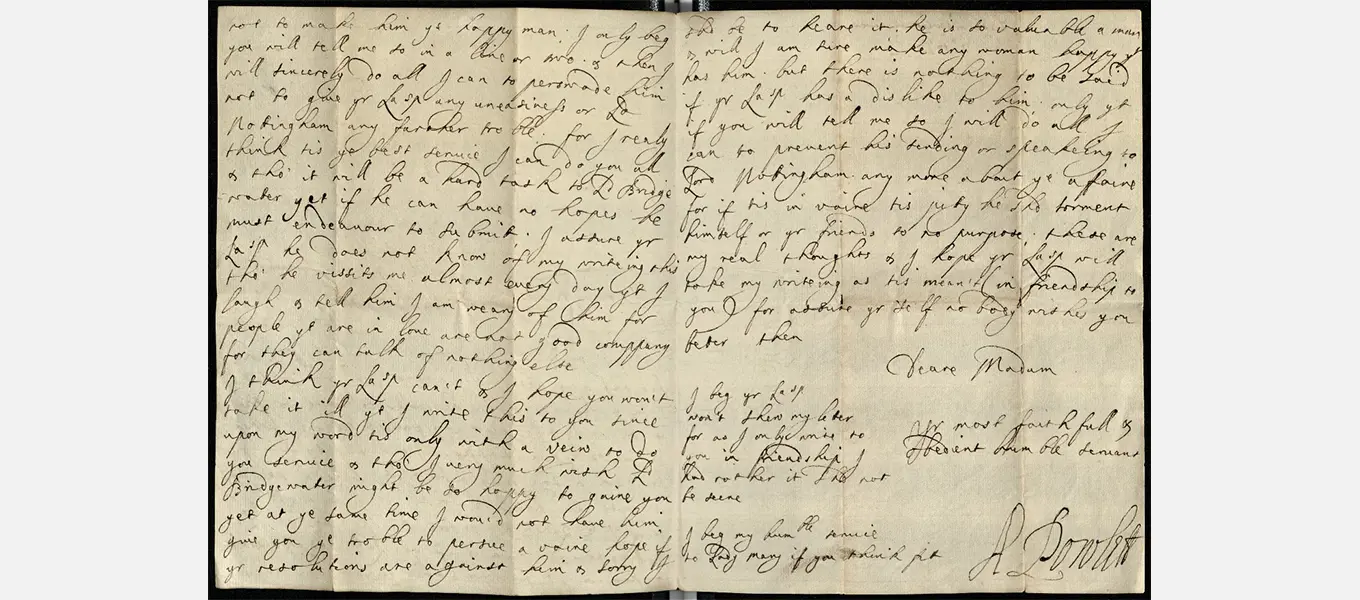

Lady Powlett to Lady Dorothy Savile, 30 December 1719 (CS1/145.2)

Some other letters in this series, come from Lady Anne Powlett, (later Duchess of Bolton) who was Lord Bridgewater’s aunt and attempts to persuade Lady Dorothy that her nephew's love is genuine and not owed to her fortune as suggested by Lady Mary (Dorothy's sister) and that Lord Bridgewater has £10,000 a year. She adds that if it is a higher title that Lady Dorothy requires, that he will soon be made a Duke and that she is sure they would be very happy together. She later asks Dorothy why she won’t accept Lord Bridgewater’s proposal:

“…he is in a sad way about it; which has put it into my head to take ye liberty to ask your Ladyship a question: before he speaks to Lord Nottingham; which is if your ladyship has an aversion to him or that for any other reason you resolve not to make him the happy man. I only beg you will tell me so in a line or two.” 30 December 1719.⁶

There is no definitive answer in the correspondence as to why Lady Dorothy did not accept Lord Bridgewater’s proposal. But it is evident riches and a dukedom were not enough to persuade her of the match.

Two years later, she married ‘the architect earl’, Lord Burlington, who had a lesser title and fortune, but a shared love of the arts. Though little is known of Lady Dorothy Savile before she became Lady Burlington, it can be argued that her individual creativity and interest in the arts was not fleeting or a side-note, it was an important-enough factor to warrant accepting a less eligible bachelor, in a time when, to quote Mark De Novellis: ‘Marriage amongst landed classes was akin to international relations… [and] the most decisive event in a woman’s life’.⁷

Sketch of Chiswick cupola by Kent (26A 35)

On the announcement of their marriage William Kent (who lived with the Burlingtons for thirty years) wrote: “I hope the Vertu will grow stronger in our house and Architecture will flourish” – recognising the important contribution Lady Dorothy would make, not just financially but perhaps creatively too.⁸

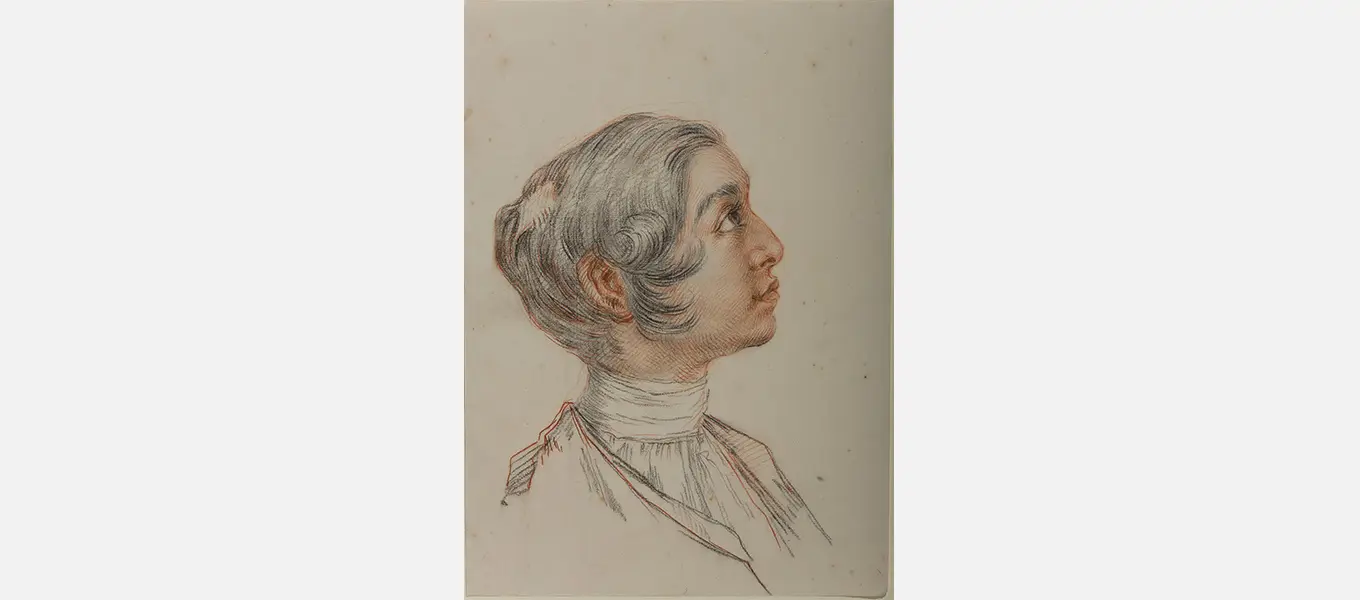

William Kent provided Lady Burlington with art lessons. As well as the thousands of letters that were passed into the Devonshire collection via the Burlingtons, some of the sketches and paintings Lady Burlington created also remain.

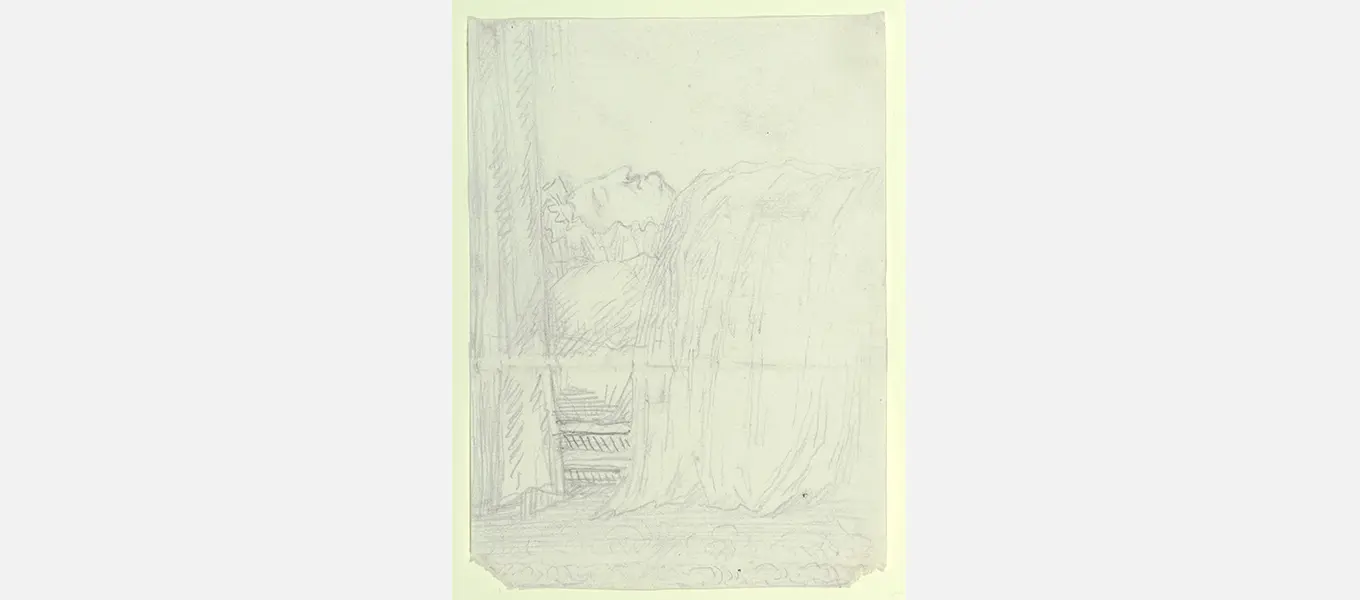

They provide an insight into Lady Burlington’s own position in a very creative environment and capture who and what she saw, including in her role as head of the household affairs, mother, host and Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Caroline. She drew and painted servants, her children, her guests such as Alexander Pope and even Queen Caroline on her death bed in 1737.

Queen Caroline on her death bed by Lady Burlington, (26 69)

As a woman she would not have had access to the formal training professional male artists underwent. A generation later, even Angelica Kauffman who was a founding member of the Royal Academy in 1768 was barred from life-drawing classes due to her sex.⁹ However, on top of her friendship with Kent, her title and position in the Royal court allowed Lady Burlington access to the Royal collection, as well as seeing the masterpieces acquired by Lord Burlington hung in her own houses.

From these resources she could copy and learn.¹⁰ Again her position and environment were key to her pursuance of her creativity.

This environment, was not a passive one in which she happened to find herself in the middle, but rather a circle that she and Lord Burlington cultivated together. Evidence in the archives shows Lady Burlington corresponded widely, keeping herself networked to this creative circle and informed of their movements, conversations and ideas.

Letters exist to and from her and William Kent; Lord Burlington; Alexander Pope; Brian and Fernandino Fairfax; Lady Isabella Finch; David Garrick; Robert Walpole; her own children Lady Dorothy and Lady Charlotte and her son-in-law Lord Hartington. All these characters and more were in some way connected to Lord and Lady Burlington as well as often others in this creative circle. And the letters from them show how Lady Burlington was central to these connections.

What these particular letters do not show is how Lord Hartington ‘had trouble with’ Lady Burlington as a mother-in-law, as has been suggested by some scholars in one of few references to her.¹¹

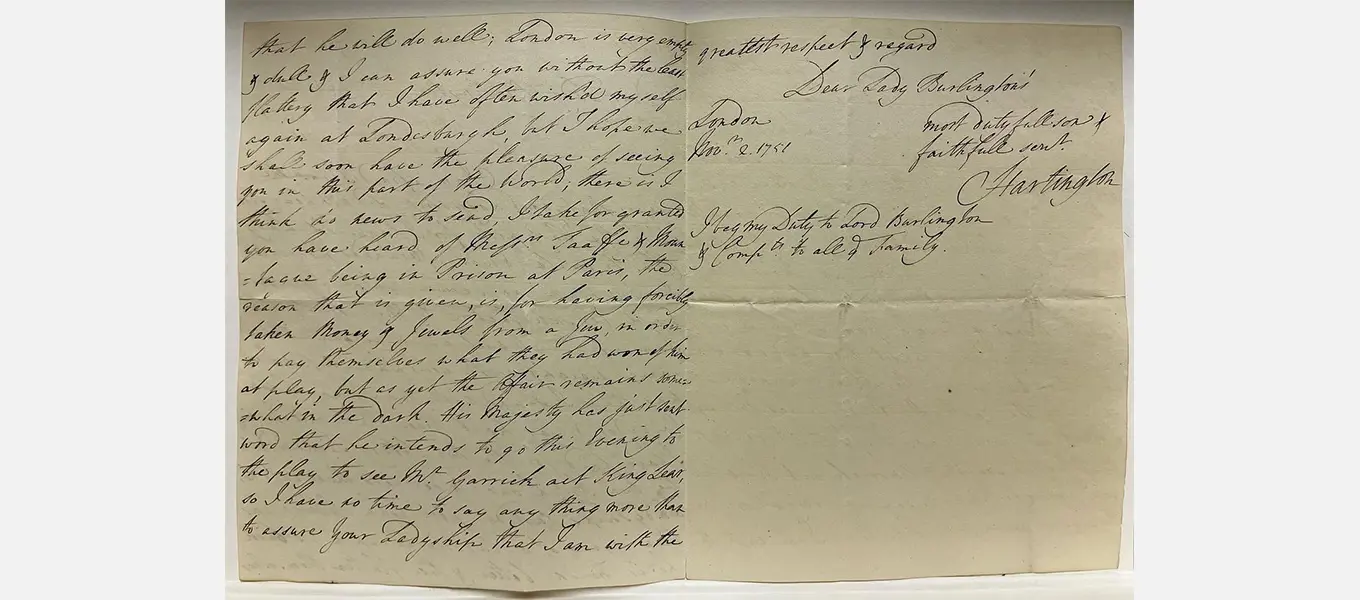

Lord Hartington to Lady Burlington, 2 November 1751 (CS1/260)

In fact when reading all the correspondence between these two it is rather touching to see how Lady Burlington became an increasingly important part of Lord Hartington’s life, especially after the death of his wife Lady Charlotte. In this period of Lady Burlington’s later life, around 1755, Lord Hartington was in Ireland as Lord Lieutenant whilst his children, little Dorothy (Lady B’s namesake) and her brothers nicknamed ‘Cann’ and ‘Dicky’, were living with their grandmother at Chiswick. In these letters Lord Hartington signs himself “Dear Lady Burlington’s most dutiful son”.

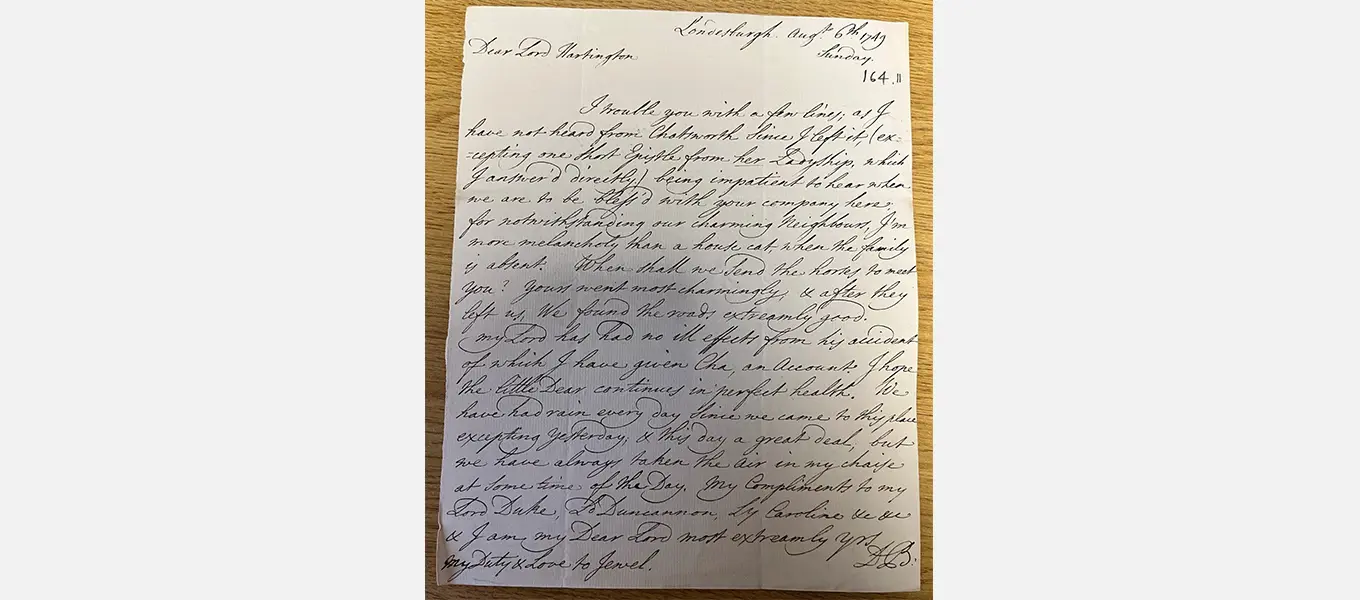

In one letter from Londesborough in 1649, Lady Burlington writes of “being impatient to hear when we are to be bless’d with your company here? For notwithstanding our charming neighbours, I’m more melancholy than a house cat, when the family is absent”.¹²

Though Lord Hartington himself may not have been as involved with the creative pursuits that surrounded Lady Burlington, he was clearly well aware of her interest and patronage of the arts. In one letter he writes that he shall describe to Lady Charlotte (who they called Jewel) – his then fiancée – the opera he had seen that evening.

And in another much later letter he mentions to Lady Burlington “His majesty has just sent word that he intends to go this evening to the play to see Mr Garrick act King Lear”.¹³ David Garrick was a friend of the Burlingtons and it was Lady Burlington who provided the dowry for his fiancé Eva Marie Veigel, the famous Viennese dancer who lived at Burlington House for a time under the patronage of Lady Burlington.¹⁴

As well as letters that illuminate Lady Burlington’s own close relationships and affection for those in her circle and her love of interacting with them, she also preserved the letters of a number of her family members.

Thanks to this practice of hers, Chatsworth Archive is furnished with correspondence of the Saviles – including letters of her grandfather, 1st Marquess of Halifax and his second wife Gertrude Pierrpont, as well as the Grand Tour letters of her uncles, Lord Eland and Henry Savile – and letters of the Finches, including Lady Isabella Finch whose house at Berkley Square was designed by William Kent.

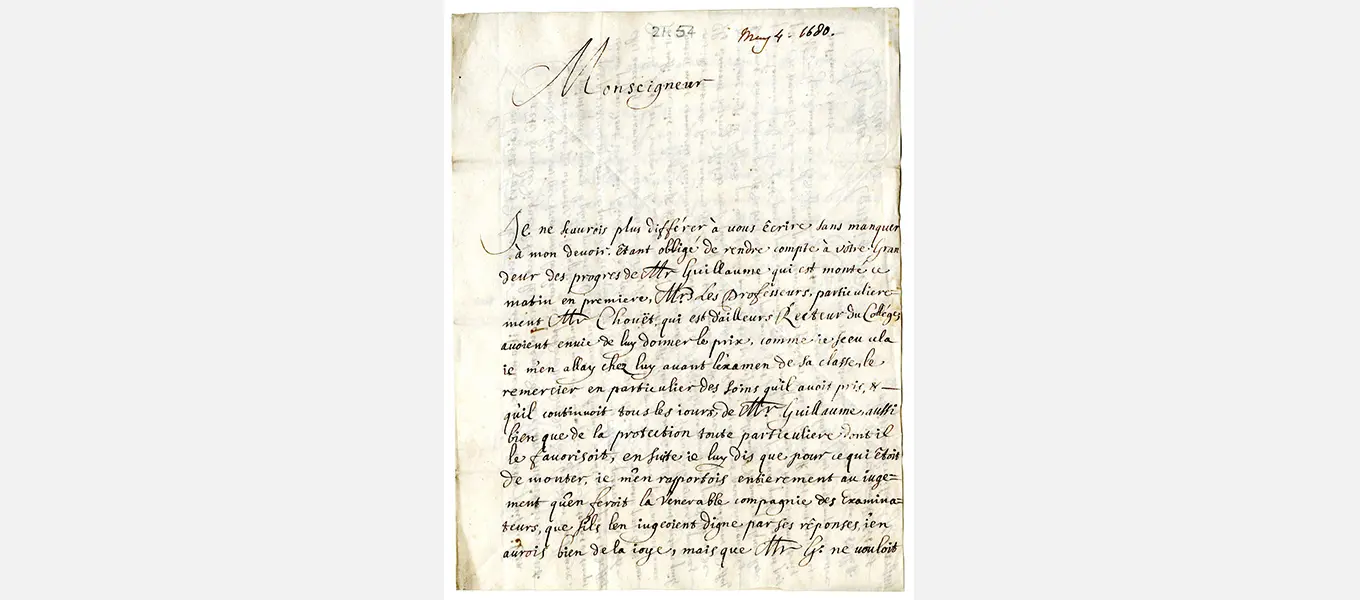

Letter from Mr Marquis [tutor to William Savile] to George Savile, 1st Marquess of Halifax, 4 May 1680 (CS1/21.54)

When one is faced with the legacy of letters treasured by Lady Burlington – who may well have been familiar with the contents of them all – it is not surprising that she was a confident and self-assured individual. Add into this rich resource, Lady Burlington’s own correspondence, one is left with the impression of a person who saw the benefit of nurturing connections and one’s environment through letter-writing. This evidence also provides insight into the thoughts, actions and conversations of the circle of people who nurtured her own creative talent. Lady Burlington’s personal legacy of letters reveals the role she played in the creative circle which has so often in scholarship revolved around the character of her husband Lord Burlington. By studying these letters we find the circle was equally in need of – and would not have existed in the same way without – Dorothy Boyle (née Savile) better known as, the Countess of Burlington.

References

- Walpole, Horace, Anecdotes of Painting in England, London: Murray, 1871 reprint, p. 383.

- De Novellis, Mark, Pallas Unveil’d – The Life and Art of Lady Dorothy Savile, Countess of Burlington (1669-1758), Orleans House Gallery, Riverside Twickenham, 1999, p. 5.

- See Mark De Novellis’s exhibition catalogue Pallas Unveil’d – The Life and Art of Lady Dorothy Savile, Countess of Burlington (1669-1758) for an examination of Lady Burlington as artist.

- De Novellis, 1999, p.5.

- Devonshire Collection, Correspondence Series 1, CS1/152.1.

- Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth Archive, CS1/145.2.

- De Novellis, 1999, p. 5.

- De Novellis, 1999, p. 5; Egerton, Judy, ‘Boyle, [nee Savile], Dorothy, countess of Burlington, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- De Novellis, 1999, p. 15.

- De Novellis, 1999, p. 15.

- Barbard, T. & Clark, J. (eds), Lord Burlington: Architecture, Art and Life, London: The Hambeldon Press, 1995, p. 286.

- Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth Archives, CS1/164.11.

- 2 November 1751, Devonshire Collections, Chatsworth Archives CS1/260.

- Egerton, 2004.